Exhibits

"Good God, I can't publish this," was the initial response of William Faulkner's publisher upon reading the manuscript of Sanctuary. Indeed, the novel was scandalously different from the author's previous works. It was intended, in Faulkner's own words, to "make money" which he badly needed to support his growing family. However, Faulkner's publisher changed his mind and by 1932 the public was avidly reading the bestselling tale of the reckless society girl named Temple Drake whose wild excesses eventually end in ruin.

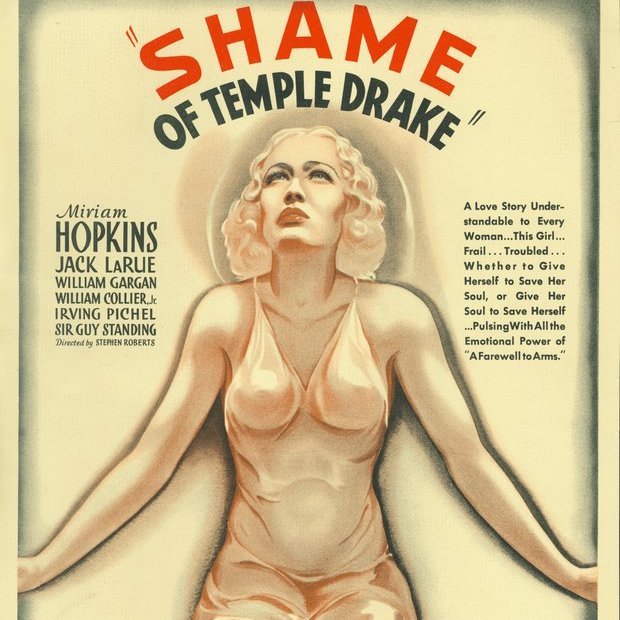

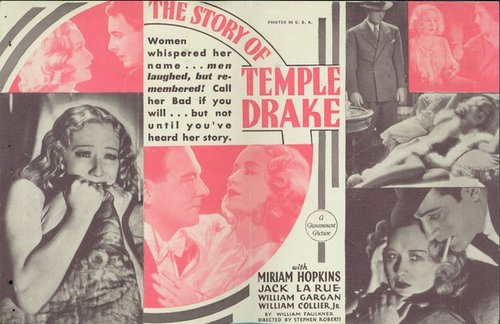

Executives at Paramount Pictures bought the rights to the work in 1932 for the sum of $6,000. Social critics lodged protests against the venture from the beginning, but the story eventually made its way to the big screen one year later. Director Stephen Roberts and screenwriter Oliver Garrett had to walk a fine line to keep as close to Faulkner's story as possible while still pleasing the censors of the Motion Picture Production Code. The film actually ends with the redemption of Temple which does not occur in the book. Featured in the display are a rare pressbook from the 1933 movie and two promotional inserts: ("Shame of Temple Drake"; "The Story of Temple Drake")

[See also: signed head shot of Ruth Ford (Ford had played Temple Drake in Requiem for a Nun; Sanctuary (1961) movie poster]

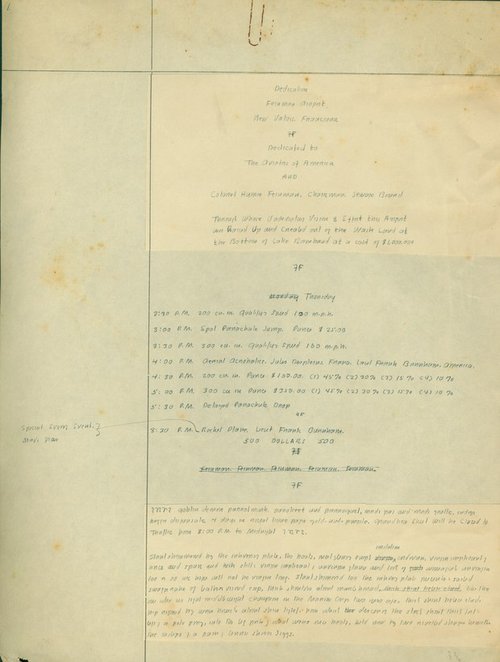

By the summer of 1934 Faulkner suffered from writers block in the writing of his opus, Absalom, Absalom and needed a new project. After discussing his problem with filmmaker Howard Hawks, he decided to write a story based upon events he witnessed at a 1934 barnstorming air show in New Orleans. Told through the eyes of an ineffectual reporter the story, which would become the book Pylon (1935), chronicled the death of a risk-loving aviator. Tragically, Faulkner's youngest brother Dean died in a place crash over Thaxton, Mississippi almost eight months after the book's release. Devastated, Faulkner blamed himself for introducing his brother to flying and selling Dean the aircraft involved in the crash.

Film studios expressed interest in the work soon after publication but it was not until the mid-1950s that Universal Pictures bought the rights for the reported sum of $50,000. Producer Albert Zugsmith convinced Universal to use the same team involved in the popular 1956 movie Written on the Wind: director Douglas Sirk and actors Rock Hudson, Robert Stack, Dorothy Malone, and screenwriter George Zukerman. Sirk's first task was toning down the sexual overtones in order to pass the censors. Released in 1957 under the name of The Tarnished Angels, the film received mixed reviews, although Faulkner reportedly liked the result.

Special Collections owns a virtually complete handwritten manuscript of Pylon written entirely in green ink. On display is one of the early pages of the manuscript entitled, "Dedication of an Airport." An image from the 1936 Ole Miss yearbook features a photograph of Faulkner with the caption, "William Falkner, novelist and aviator." A copy of the original three-sheet poster is also featured.

Based on The Hamlet (1940), Faulkner's first volume of his Snopes trilogy, The Long Hot Summer (lobby card; sheet music) features an all-star cast that includes Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Lee Remick, and Orson Welles. The title was not the only component to undergo a transformation from page to screen, as Faulkner's main character, played by Paul Newman, changed names from ‘Flem Snopes' to ‘Ben Quick.' Newman captivated audiences with his portrayal of a man determined to enter into polite society through marriage to the daughter of the wealthy Will Varner. Newman's success derived in part from the screenwriters: Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank, Jr., concerted efforts to keep the character of Ben Quick true to Flem Snopes' ruthlessness while still retaining some humanity. For example, the book's Flem sells unbroken horses to the townspeople of Frenchman's Bend-swindling most of the village in the process. In the film, Ben also sells horses, but when an overwrought wife of one of his victims begs him to refund the money, he obliges.

Filming occurred in Clinton, Louisiana due to its small-town atmosphere and similarities with the landscape described by Faulkner. Newman checked into the local hotel a few days prior to the first shoot in order to study the speech patterns and customs of the people, ironically signing the guestbook as ‘Ben Snopes.' His research reaped rewards in the form of the "Best Actor" award at the 1958 Cannes Film Festival.

In his 1959 article for Films in Review, producer Jerry Wald, commented on the difficulties faced by screenwriters writing scripts based upon books like The Sound and the Fury. Wald commented, "Adapting a literary work to the screen...is primarily an attempt to capture in visual and dramatic terms the spirit, rather than the letter, of a work." Many critics of the 1959 film The Sound and the Fury argue that it completely ignores the message or even the spirit of Faulkner's 1929 novel. Indeed, the screenplay drastically altered several main themes: the tragic Quentin (called Howard in the film) does not commit suicide but returns home an alcoholic; Benjy and Quentin's sections of the novel are deleted and the characters of Dilsey and Jason are distorted; Caddy's daughter Quentin actually marries Jason in one of the most complicated twists of familial genealogy imaginable. But the most obvious change is that of the character of Jason himself, played by Yul Brynner. Acknowledged by Faulkner to be "inhuman" and a "bastard in behavior," Jason is reformed in the film into someone acting in the best interests of the Compson family.

On display are two items relating to the film: the soundtrack for the film featuring music by Alex North and a reproduction of a Belgian poster for the film with its translated title, Le Bruit et la Fureur.

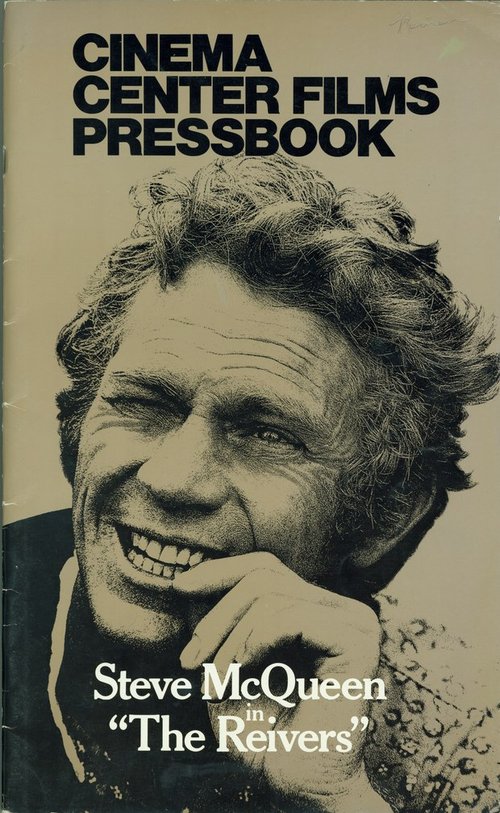

Considered by most critics as one of the best Faulkner film adaptations, The Reivers (1969) was shot on location in Carrollton and Greenwood, Mississippi. Coincidentally two actors in the film were veterans of the film adaptation of Intruder in the Dust (1949), Will Greer and Juano Hernandez. The screenplay for the film also featured Faulkner screenwriter veterans, Irving Ravetch and Harriet Frank who had previously worked on The Long, Hot Summer (1958) and The Sound and the Fury (1959).

On display are promotional items relating to the film including a Japanese pressbook and original photographs of the filming in Mississippi: (post office in "Jefferson, Miss."; horses and mules; McCaslin's stable; the Winton flyer)

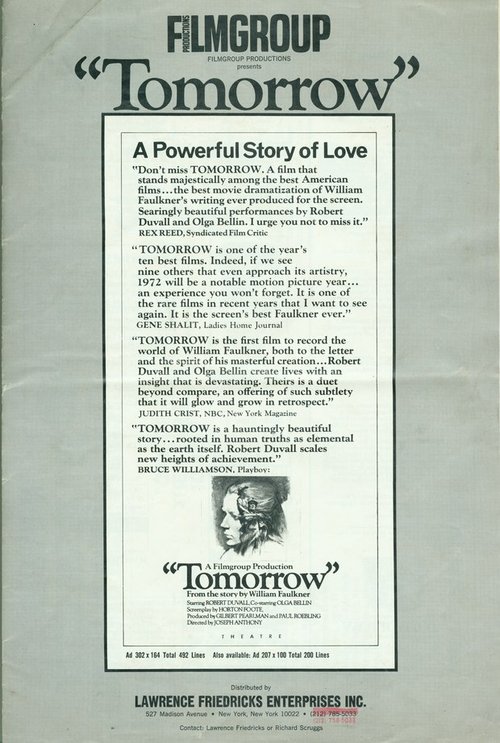

Based on a Faulkner short story, "Tomorrow" reappeared in the author's 1949 short story collection Knight's Gambit. The original story is the tale of a lonely farmer, Jackson Fentry, who becomes the foster father to a young baby who he names "Jackson and Longstreet." After a few years, the birth family returns to claim the child who grows into a mean bully named Buck Thorpe. In the process of trying to run off with a young girl, Thorpe is killed by her father, Homer Bookwright. Ironically enough Fentry is one of the jurors in the ensuing trial against Bookwright. Fentry hangs the jury because he cannot forget the baby he once knew and loved.

The road to the film Tomorrow was a long one -- Faulkner himself at one time played with the idea of developing the story into a screenplay. But the first to pen the story for film was Horton Foote, the Oscar-winning screenwriter for To Kill a Mockingbird. Foote had experience adapting Faulkner on the small screen with the teleplay for Old Man (1958). In 1960, Tomorrow appeared live on the CBS Playhouse 90 series and proved extraordinarily popular. This success prompted well-known stage director, Herbert Berghof, to co-write a theatrical production of the work with Foote. The play opened in 1968 with a little-known actor named Robert Duvall playing the lead. Two film producers in the audience on opening night decided to make a film using Foote's screenplay and Robert Duvall.

Hearing about the project, a Tupelo woman wrote to the producers to suggest her hometown as a film location, and the producers decided to adopt her suggestions as the north Mississippi area contained many of the necessary exterior sites.

Despite a limited distribution, the film was a critical success. Critic Rex Reed proclaimed it, "a film that stands majestically among the best American films." Gene Shalit wrote that, "Tomorrow is one of the year's ten best films...It is the screen's best Faulkner ever."