Exhibits

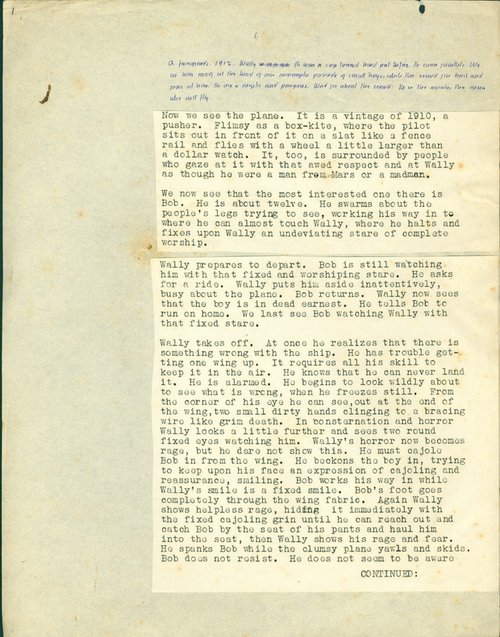

Reportedly, Tallulah Bankhead instigated William Faulkner's film career. During a 1931 visit to New York the sultry southerner approached the author to write a screenplay with a starring role for herself. Faulkner was broke and liked the idea of "easy money." In May of the following year he reported for work on the MGM studio lot. His career began inauspiciously when he left the screening room of his first project, Flesh, after only a few minutes stating that he "knew how it would turn out." However, Faulkner soon settled down to work producing preliminary outlines for films, otherwise known as movie treatments. One of his earliest treatments, Flying the Mail, revised an earlier work written by Ralph Graves and Bernard Fineman concerning a father and son pilot team. MGM never produced the film, but segments of Faulkner's treatment remain. One of these fragments is on display, a handwritten text with several discrete strips of typewritten sections pasted onto the page.

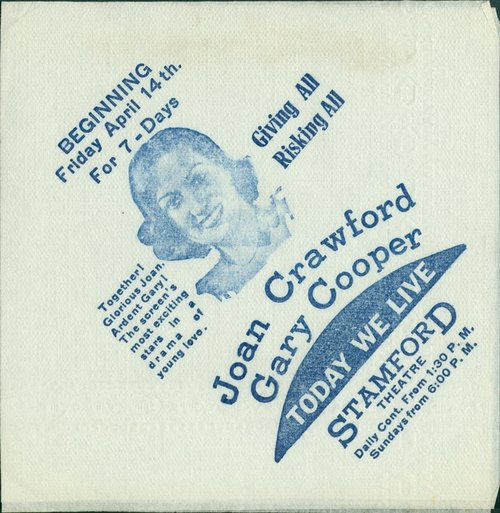

Famed director Howard Hawks admired Faulkner's short story "Turn About," which appeared in a 1932 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, so much that he immediately signed the author to a contract to convert the piece into a movie. Set in war-torn Europe, Faulkner easily adapted his story to the big screen with only minimal alterations, one being a title change to Today We Live. Hawks felt the film was the perfect venue to showcase the talents of a young Joan Crawford, although the actress had serious doubts about the project. MGM pulled out all the stops advertising the 1933 film and this display features a two-page advertisement as well as a promotional napkin. Illustrating its international allure, the display case also contains a Danish program and Danish insert for the film.

During this time on the lot, Faulkner often felt uncomfortable and homesick. He felt isolated from Hollywood and nothing illustrates this more that an encounter he reportedly had with famed actor Clark Gable in 1932. Howard Hawks invited Faulkner and Gable to go dove hunting. While tramping across the countryside, Gable reportedly asked Faulkner to list the best living writers. Faulkner replied, "Ernest Hemingway, Willa Cather, Thomas Mann, John Dos Passos, and William Faulkner." Gable replied with surprise "Do you write, Mr. Faulkner?" Faulkner sardonically answered, "Yes, Mr. Gable; what do you do?"

In 1936 Hawks asked Faulkner to revise a 1932 French film entitled Les Croix des Bois (Wooden Crosses) based on the novel by Roland Dorgelès and directed by Raymond Bernard. Part of the original's allure was its startling realism - all of the actors were French veterans of World War I and Hawks felt that a revised version could bring the story to a wider audience. Faulkner and Joel Sayre wrote a screenplay initially titled Wooden Crosses, then Zero Hour, and finally The Road to Glory. On display is a one-page sample from Faulkner's 140-page, handwritten working draft with the title Wooden Crosses. Also featured is 20th Century-Fox Corporation's illustrated pressbook for the film in which Faulkner shared screenplay credit only with Joel Sayre, although the film's director Howard Hawks and writer Nunnally Johnson also contributed to the final product.

Critical comparison of screenplay drafts with the final film product indicates just how little Faulkner contributed to several of the films he worked on during the 1930s and 1940s. Directors and producers involved in such films as Banjo On My Knee (1936), Slave Ship (1937), Submarine Patrol (1938), and Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) felt that he spent too much time fleshing out characters and their troubled pasts. However, Faulkner made more substantial contributions to films such as Air Force (1943) (photograph; lobby card) and The Southerner (1945).

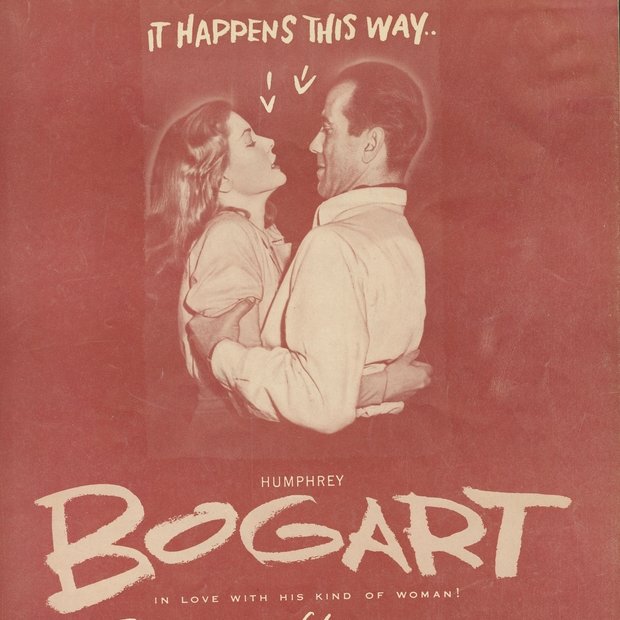

The most memorable Faulkner/Hawks productions of this period were the adaptations of Ernest Hemingway's To Have and Have Not (1944) (pressbook) and Raymond Chandler's The Big Sleep (1946). Initially reluctant to permit a film adaptation of his short story, Hemingway eventually agreed, and Faulkner was chosen to write the screenplay. Faulkner changed the protagonist, Harry Morgan, from a Key West rum runner to an anti-Vichy smuggler on Martinique during World War II. This transformation allowed Hawks to enhance the similarities of Humphrey Bogart's character Rick from the recently released Casablanca (1942) with that of Morgan. It also provided Faulkner an opportunity to display his anti-fascist beliefs. The quick-witted scenes often resulted from Faulkner taking the recently finished script pages directly to the set and the addition of ad-libbed lines by the actors. Final screenplay credit went to both Faulkner and Jules Furthman, and this display case features the earliest published form of the Faulkner-Furthman text in a cheaply produced Japanese publication with the complete dialogue in both Japanese and English.

If Faulkner had his way, The Big Sleep would have an entirely different ending with the Philip Marlowe character, played by Bogart, tricking the murderer into taking a bullet intended for the private detective. However, the film censors rejected Faulkner and co-author Leigh Brackett's version because the Production Code would not permit the leading man to "take the law into his own hands." The studio used an alternate ending, written by author Jules Furthman, where the villain enters a mental institution.

Faulkner's script-writing career began to slow down in the late 1940s and early 1950s. Increasingly, what little screenwriting he attempted was ignored. The studio, for instance, completely abandoned Faulkner's screenplay for the adaptation of Stephen Longstreet's novel Stallion Road (1945). The book's author had to complete the task for the 1947 film starring future U.S. president Ronald Reagan. Faulkner's version remained unpublished until 1989 when it was released by the University Press of Mississippi.

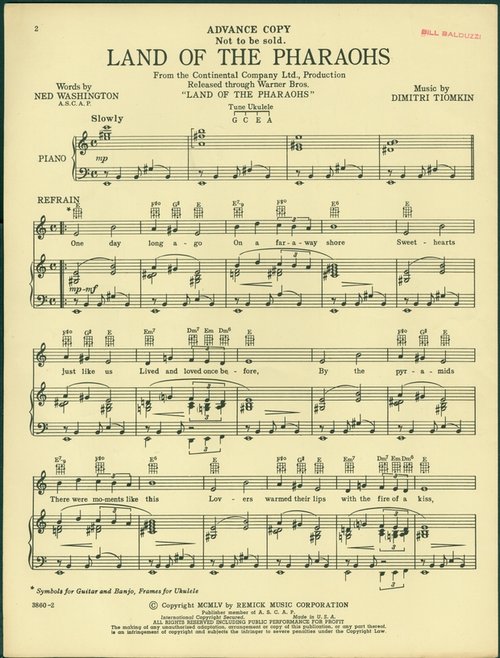

The last two scripts Faulkner wrote for Hawks were The Left Hand of God (1955) and Land of the Pharaohs (1955). Hawks dumped Faulkner's screenplay of The Left Hand of God due to warnings from a Catholic priest that the risqué subject matter would startle moviegoers. Land of the Pharaohs stars the young actress Joan Collins, as the evil Princess Nelliter. After this project Faulkner worked occasionally for television but never returned to film.