Student Work

Reconstruction and Great Depression

By: Dustin Wright

Photo credited to website Only In Your State

Mississippi Puts the Mis in Misfortunate

Often when an economic disaster happens, the people that suffer most are the everyday people in society. When the Civil War started, many people in the south, including many poor farmers turned soldiers, felt as though they were being asked to fight and support a rich man’s war. In fact, a study of the 1860 South Carolina census found that among the deserters 56.8 percent owned no land, only 13.6 owned any slaves, and only 1 person owned more than 20 slaves.[1] Nevertheless, the south suffered the repercussions the hardest after Jefferson Davis and the planters had lost their war and squandered the south’s resources and economy during the war and Reconstruction. The same can be seen after the Great Depression in 1929. Because of the greed and mismanagement of the banks and Wall Street, the entire nation suffered the worst economic disaster in its history. It would be plagued with millions of unemployed people and starving bread lines until the start of World War II. One study shows that “In the first four years of the depression total income fell around 40 percent as unemployment pushed towards 25 percent.”[2] In both of these cases one of the most affected areas was Mississippi, which in many ways is still recovering from the Civil War and from Reconstruction, and which was doubly affected by the Great Depression.

With the framework of Reconstruction and The Great Depression in mind and looking at the daybook accounting ledgers of the Neilson’s Department Store, one can get a window into the everyday lives of the people of Mississippi during these time periods. The findings are somewhat surprising. During both periods, there is little evidence that people stopped spending in Oxford. Even with the difference in value between those time periods and today, there are steady purchasing transactions in both periods.

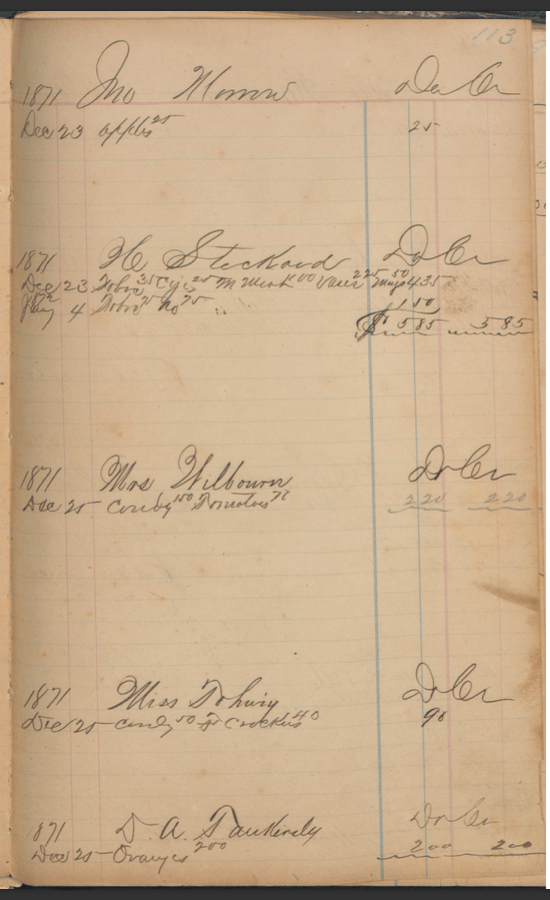

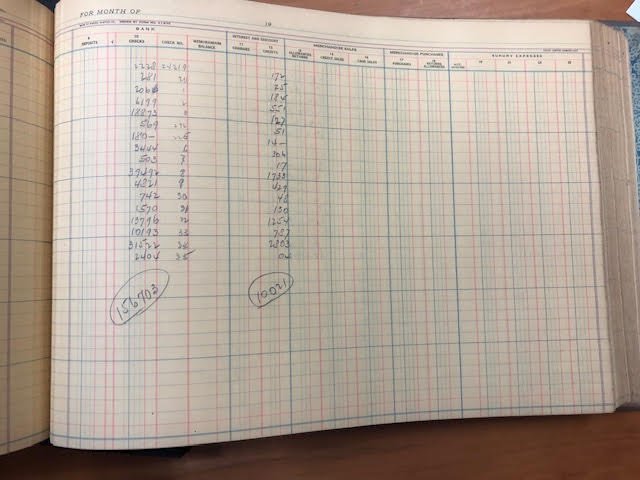

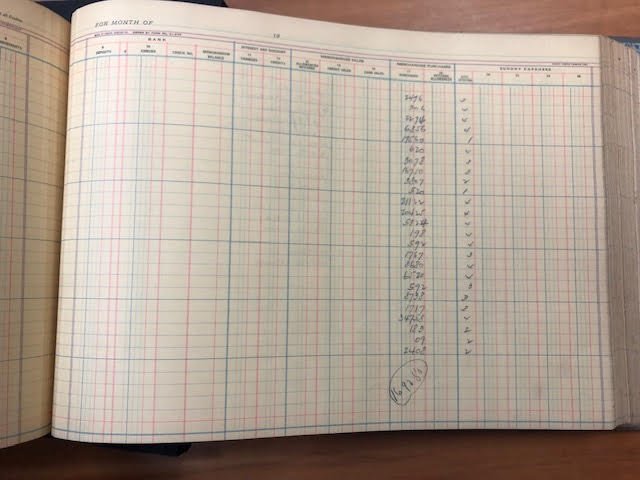

In 1871 people in Oxford stopped in and regularly indulged themselves with oysters, candy, port, and ale. There are instances of extravagant orders of such items in very large quantities, and then very small orders of one or two items at a usual cost of one or two dollars.[3] This might be evidence of people only able to indulge themselves in very small quantities or on special occasions. It may also be evidence of an upper class that was not affected to a large extent by the Civil War or Reconstruction and instead were able to prosper while many were not. In 1929 after October 24th (Black Thursday) there are only accounting numbers to base inferences on. The only affect that can be seen is a steady decline in overall sales in cash and a very large decline in credit sales of about two-thousand dollars from the previous days.[4] This may be an accounting instance of people being wary or unable to purchase anything with credit. They may have taken their money out of the banks (and possibly failed). They could have been unable to buy anything altogether, or the store could have turned people away. Whatever happened there was a noticeable drop in amount of sales. Yet it did not last for long, and Neilson’s was able to not only stay open but flourish. Sales continued throughout the Great Depression. Although there are instances of “bad checks” or instances of coming up “short”, sales appear steady and sometimes extravagant in an apparently usual Oxford way.

Ledger 4, 1871 Page 48 from Neilson’s Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Libraries.

Ledger 4, 1871, Page 113 from Neilson’s Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Libraries.

Ledger 38, October 29, 1929 from Neilson’s Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Libraries.

Ledger 38, October 29, 1929 from Neilson’s Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Libraries.

[1]Doyle, Patrick J. “Understanding The Desertion Of South Carolinian Soldiers During The Final Years Of The Confederacy.” The Historical Journal56, no. 3 (2013): 657-79. http://www.jstor.org.umiss.idm.oclc.org/stable/24529089.

[2]Schmitz, Mark, and Price V. Fishback. “The Distribution of Income in the Great Depression: Preliminary State Estimates.” The Journal of Economic History43, no. 1 (1983): 217-30. http://www.jstor.org.umiss.idm.oclc.org/stable/2120285.

[3]Ledger #4, Day Book Ledger 1871, p. 48 & 113 Neilson’s Department Store Ledger Collection, Departme nt of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Library

[4]Ledger #38, Day Book Ledger 1928-1929, Oct. 29, 1929, Neilson’s Department Store Ledger Collection, Department of Archives and Special Collections, The University of Mississippi Library