Mississippians

Nobody’s Free Until Everybody’s Free: Fannie Lou Hamer and the Struggle for Equality

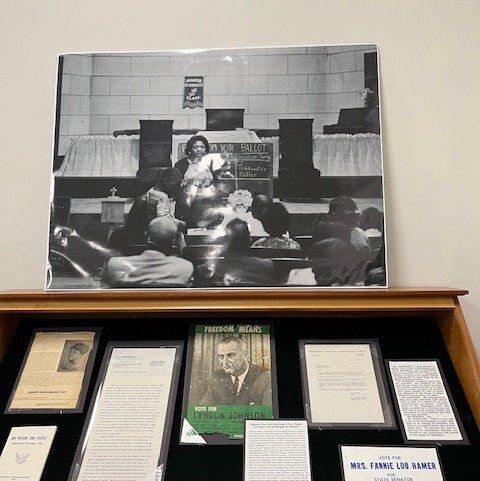

Fannie Lou Hamer, a major figure in the Civil Rights Movement, was born into a Montgomery County, Mississippi sharecropping family in 1917. In 1944 Hamer began working on the Marlowe Plantation in Sunflower County where she worked for the next eighteen years until she was fired in 1962 after attempting to register to vote. In 1964 Hamer became one of the founding members of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), established as an alternative to the state's all-white loyalist Democratic party. Hamer served as Vice-Chair of the MFDP at the 1964 state convention, and that same year she unsuccessfully attempted to challenge loyalist Jamie L. Whitten for Congress, although her name was not included on the ballot. Hamer did, however, run in a special counter-election held by the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee that was open to all candidates. In this election, known as "Freedom Vote," Hamer won. In late 1964 Hamer again received national recognition when she challenged the election results on the grounds that African American Mississippians were prohibited from voting. She garnered international notice during that year’s Democratic National Convention, giving impassioned testimony about Southern segregation as she unsuccessfully attempted to force the Party to recognize the MFDP.

The archival documents showcased in this display chronicle Hamer’s unyielding lifetime political activism, including a tragic letter about her own forced sterilization written to Senator James O. Eastland, accusing the politician of “sickening” behavior. The featured facsimile of the Congressional Record (3 February 1965) provides additional context. An original “Notice of Intention to Contest Election” sent to Representative Jamie L. Whitten is also featured in this case, among several other significant archival documents dating from Hamer’s lifetime.

In the display case:

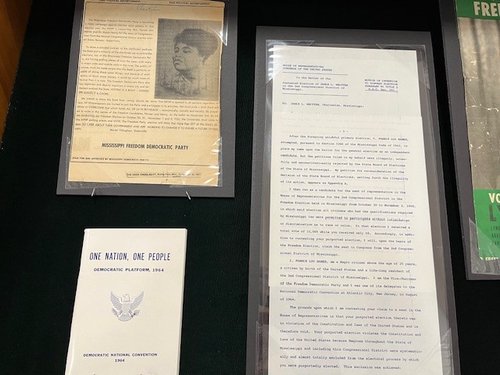

- Political Advertisement for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party which ran in The Deer Creek Pilot (Rolling Fork, Miss.) on 30 October 1964.

- One Nation, One People: Democratic Platform, 1964. Democratic National Convention (1964)

- Contested-Election Case of Fannie Lou Hamer v. Jamie L. Whitten from the Second Congressional District of the State of Mississippi. Eighty-Ninth Congress. (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1965)

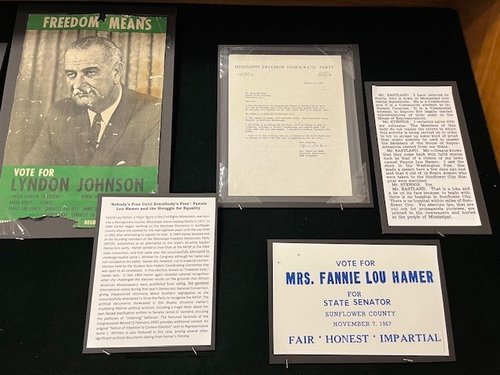

- Poster, "Freedom Means Vote for Lyndon Johnson", Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964)

- Facsimile of the Congressional Record (3 February 1965) in which Senators James O. Eastland and John Stennis dispute claims made by Fannie Lou Hamer about her own forced sterilization. (see page 1947)

- Letter from Fannie Lou Hamer to Senator James O. Eastland on letterhead from the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (12 February 1965) responding to his remarks about her in the Congressional Record (3 February 1965)

- Campaign card, "Vote for Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer for State Senator, Sunflower County, November 7, 1967. Fair, Honest, Impartial"

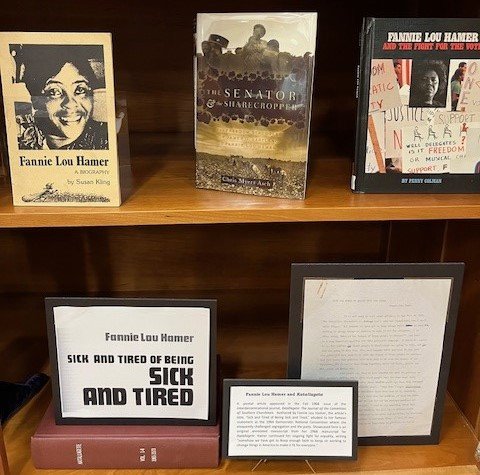

- Fannie Lou Hamer: A Biography / Susan Kling

- The Senator & the Sharecropper / Chris Myers Asch

- Fannie Lou Hamer and the Fight for the Vote / Penny Colman

- "Fannie Lou Hamer: Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired" (Katallagete: The Journal of Southern Churchmen, Fall 1968)

A pivotal article appeared in the Fall 1968 issue of the interdenominational journal, Katallagete: The Journal of the Committee of Southern Churchmen. Authored by Fannie Lou Hamer, the article’s title, “Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired,” alluded to her famous statement at the 1964 Democratic National Convention where she eloquently challenged segregation and the party. Showcased in this display is an original annotated manuscript from her 1968 manuscript for Katallagete. Hamer continued her ongoing fight for equality, writing “somehow we have got to keep enough faith to keep on working to change things in America to make it fit for everyone.”

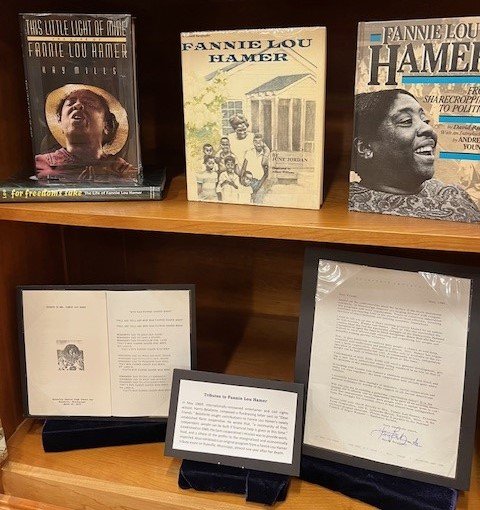

- This Little Light of Mine: Fannie Lou Hamer / Kay Mills

- For Freedom's Sake: The Life of Fannie Lou Hamer / Chana Kai Lee

- Fannie Lou Hamer / illustrated by Albert Williams

- Fannie Lou Hamer: From Sharecropping to Politics / David Rubel with an introduction by Andrew Young

- Program from "Tribute to Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer" held at Ruleville Central High School Gym in Ruleville, Miss., March 10, 1978. Includes poem, "Why was Fannie Hamer Born?"

- Letter from Harry Belafonte to "Dear Friend", to fundraise for the Freedom Farm Cooperative, May 1969

In May 1969, internationally-renowned entertainer and civil rights activist, Harry Belafonte, composed a fundraising letter sent to “Dear Friends.” Belafonte sought contributions to Fannie Lou Hamer’s newly established farm cooperative. He wrote that, “a community of free, independent people can be built if financial help is given at this time.” Established in 1969, the farm cooperative’s mission was to provide work, food, and a share of the profits to the marginalized and economically imperiled. Also exhibited is an original program from a Fannie Lou Hamer tribute event in Ruleville, Mississippi, almost one year after her death.