Mississippians

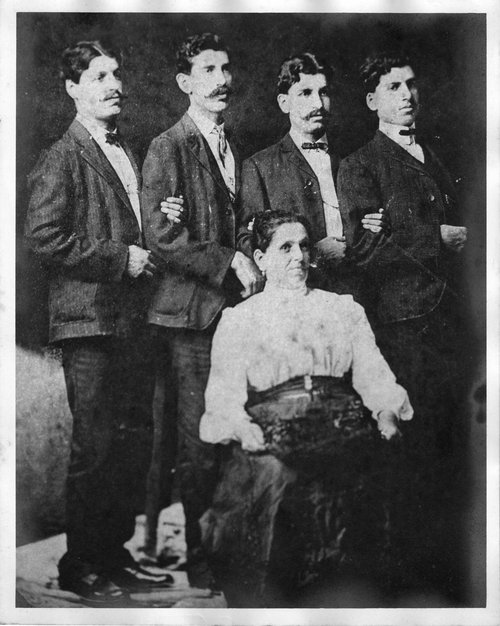

The Shamoun family in Syria prior to immigrating to the United States.

Making the Journey

Between the 1880s and the end of World War I, a combination of famines, epidemics, extreme poverty, and religious and political genocide had led to more than 100,000 Lebanese deaths in the Mount Lebanon region of Ottoman Empire-controlled Syria. During that period, more than 100,000 Lebanese residents of the predominantly Christian region participated in a mass emigration that scattered them across the globe to places such as Australia, Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. While most of these Lebanese intended to emigrate only until conditions at home had gotten better and they had acquired enough money to improve the quality of life for their families, many eventually realized that the life of an emigrant in the Unites States was preferable to their lives on what was commonly known as “the Mountain.”

Mississippi was one such place the Lebanese migrated to during this first wave of Lebanese immigration across the globe. The earliest report of a Lebanese immigrant entering the Mississippi mahjar (roughly translated from Arabic as “the land of immigration”) is of young Elias Naseef Fattouh, from the coastal village of El Monsif. Traveling alone and disembarking in the port of New Orleans in 1884, Elias knew he needed to make contact with other Syrians, so he stood on the dock and repeatedly cried out, “Kibbee, kibbe, kibbee!!!” (Kibbee is commonly considered the national dish of Lebanon—a mixture of ground lamb, bulgur wheat, and spices; anyone who had lived in Mount Lebanon or Syria would have undoubtedly understood Elias’s cry.) A Syrian merchant soon approached him and offered to help by supplying him with enough merchandise to begin peddling. Shortly thereafter, Elias found himself traveling the Louisiana and Mississippi landscape northward along the Mississippi River with a suitcase full of notions and household necessities to peddle to rural farms and in small towns. Elias walked the rural roads peddling his wares for a few years, and after saving enough money and acquiring a bit of credit, he was able to open his own dry goods store in the small town of Hermanville, Mississippi, becoming the first-known Lebanese immigrant to settle in the state. Other Lebanese immigrants followed Elias to the area and set up shops and home bases out of which to peddle, and within a few short years other families from the Mountain immigrated to Mississippi. By the turn of the century few were returning to the Mountain for good, although members of most families made occasional trips between the Delta and Syria.

In 1892 Commour Ellis immigrated to the New London, Connecticut, from Mount Lebanon, Syria, with sons George and Michael. In 1901 she and her five sons moved to Meridian, Mississippi, where they joined her brother. (Commour’s son John is not pictured.) They later, in 1908, moved to Port Gibson, Mississippi, where they opened a mercantile business on Main Street. Commour Ellis (seated) and sons (left to right) James, George, Michael, and Sam.

The Life of a Peddler

By the end of the nineteenth century, Vicksburg’s Warren County could boast more immigrants than any county in the state. Between 1822 and 1906, the Warren County Circuit Court processed 666 total immigrants. Some of the Lebanese immigrants were opening stores in town, but many of them had to make do peddling to outlying farms before they could afford to make the larger investment of business ownership. Like Elias Fattouh and his family, the vast majority of these first-generation Mississippi Lebanese started out by peddling goods door to door to black and white farm families across the Delta. Although they were familiar with farming and farming practices, this original generation chose to neither farm nor work in the fields. Sharecropping in Mississippi was hardly lucrative, and the advantages of peddling were numerous in comparison. Unlike many sharecroppers in the region, peddlers could avoid falling into peonage, and they could begin work right away. No training was necessary, and advanced English-language skills were not essential. The products they sold—which included everything from notions like pins and needles and buttons to lace, bolts of cloth, kitchen utensils, jewelry, perfume, fancy mirrors, bric-a-brac, and holy items, such as rosaries and crucifixes—could sell themselves. Also, peddling suited the independent Lebanese nature. Peddlers operated on their own terms, without having to answer to an overseer or submitting to the daily confinement and drudgery of factory work, as was often the case in the cities of the Upper Midwest and Northeast. Gregory Thomas of Vicksburg, whose grandfather came to Mississippi from Lebanon in 1920, recalled, “I remember my grandfather always telling me, ‘Son, I don’t care if you have to sell peanuts on the street, you work for yourself. Don’t make another man rich.’”

But the peddling life was far from easy. Chafik Chamoun of Clarksdale, whose grandfather peddled around Brookhaven, Mississippi, in the late 1800s, discussed his grandfather’s work: “Oh, they go probably about twenty-five, thirty miles, walk, and they spend the night in the black people’s homes. They ain’t got no vehicle, no donkey, no horse, nothing. They were tough. They put something on their back, and they go house to house.” As such, a peddler’s store encompassed the entire countryside, come rain or shine. If a peddler was unable to secure lodging for the night in a farmer’s home or barn, he or she slept under the stars. And since it was necessary to draw an income year-round, pack-peddlers preferred a climate that accommodated year-round outdoor work. In addition to the accommodating weather, the Mississippi Delta provided a large rural market for pack-peddlers, and during the busy farming seasons, men and women alike found shopping from peddlers especially convenient. Farmers who lived in isolated areas found it more convenient to buy goods from a peddler than spending a day traveling into town.

As a means of retaining ties to their own culture, these peddlers were part of an informal network of Lebanese immigrants who swapped stories and news from the Mountain. Some even traded subscription-available, American-published, Arabic-language newspapers among each other, such as Al-Bayan (New York), Al-Hoda (New York), and Syrian World (also New York). They, often with their families, formed small peddler settlements in places like Hermanville, Brookhaven, Greenville, and Vicksburg. Some features of Lebanese culture were easily enough preserved. Parents spoke Arabic in the home almost exclusively, and many of the spices and ingredients for Lebanese foods, such as cinnamon, various grains, onions, peppers, squashes, mint, chicken, and beef were readily available and part of daily food consumption. Immigrants brought musical instruments to America, and for peddlers on the road and within Lebanese settlements, music was a chief form of entertainment. Through music, language, and food, as well as through the community of their families and kinsmen, these immigrants could bring with them to the mahjar those cultural elements that they had most treasured on the Mountain. As the number of Lebanese immigrants flocking to the Mississippi Delta grew, it was less important for them to return to the Mountain to maintain their ethnic culture and identity. By the late years of the first decade of the twentieth century, many peddlers were sending for their entire families and setting down roots across the Mississippi Delta.

Setting down Roots

As the number of Lebanese immigrants flocking to the Mississippi Delta grew, and as those newcomers acquired more and more capital, it was less important for them to return home to maintain an ethnic culture. Fewer immigrants sent their money back home to their families, deciding that life in Mississippi was far and away a better life than in Lebanon. Instead, by the late years of the first decade of the twentieth century, many peddlers were sending for their families and beginning to set down roots in town. More and more Lebanese immigrants were fleeing Mount Lebanon and coming to Mississippi where friends and relatives had already gotten a large whiff of the sweet smell of success. Yet, at this time, for a number of reasons, the occupation of peddling was in a period of steady decline. One reason, perhaps, was that over time families grew larger, necessitating a less-mobile, more-stable homeplace for the growing family. Another reason was that the racial and economic climate for black croppers in the Mississippi Delta was declining rapidly as a result of the consolidation of the centralized business plantation. Ultimately, what that meant was that more money was in fewer people’s hands. Because of the racial terror to which blacks were being subjected, the years between 1915 and 1920 saw the mass exodus of 100,000 blacks from the state. The stream of cash that had been flowing into the pockets of peddlers was now drying up.

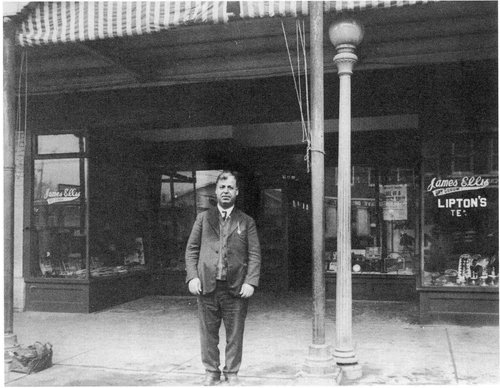

The pioneer peddlers had done well in saving money, though, and as their rural customer base steadily dwindled, they abandoned the long and lonely life on the road and settled down in Delta towns and back into family life, taking the next logical step in the path of the merchant: they opened grocery and dry goods stores. For example, James (Jim) Ellis, one of the five sons of Commour, had peddled around central Mississippi for several years before opening a general merchandise store with his brothers, who had also peddled, in Port Gibson. The brothers lived together above the store until each got married, gathered more savings, and moved into their own homes. They collected a sizable amount of real estate, and in 1927 Jim’s brother Mike built and opened a dry goods store of his own; his other brother George opened a dry goods store and grocery at around the same time. Jim’s third brother, Sam, moved to Texas to open his own business. The Ellis brothers’ sister Nazera, married a Lebanese man named George Thomas, and they opened a grocery store behind their house on College Street.

James Ellis in front of his dry goods store in Port Gibson. The building was originally the Washington Hotel in the early 1800s.

The Lebanese Mississippian Identity

It would seem that the Lebanese people, in a relatively short amount of time, were accomplishing the American dream, and in a large sense they were. The arguable downside was that the process of Americanization was gaining a stronghold on the American-born children of immigrant parents, despite the group’s slow acceptance into the dominant white Mississippian culture. Lebanese youth and adults alike nevertheless adopted American dress and participated in “American” cultural activities, and although most Lebanese immigrants wanted to instill within their children a Lebanese identity, they also knew that any overt difference between Lebanese children and children of white Mississippians would only slow the process of assimilation into the economically and socially white Mississippi culture. Yet, slowly, with each successive generation, the Lebanese were leaving behind their “otherness” as a result of increased intersocial contact and an ever-increasing distance from the homeland.

Lebanese parents have nevertheless largely succeeded in preserving some sense of Lebanese identity within their children. At the dinner table Lebanese children gain a love and appreciation of Lebanese food, and in the kitchen they learn to make tabouleh, roll grape leaves, and bake kibbee. Naming patterns continue, with the first-born son being named after the father and the second son taking the first names of the grandfathers. At special events, such as weddings and baptisms, guests play traditional music with traditional instruments and dance traditional dances, such as the dabke. As well, Lebanese families maintain a vigorous religious life that reflect their Christian religious practices on the Mountain.

As this Lebanese in Mississippi oral history project shows, pride in a Lebanese heritage has prevailed, and the history of the Lebanese past remains ingrained in the collective memory of Lebanese Mississippians. Older generations continue to pass down stories of our ancestors, and those stories become more meaningful with each telling.

—James G. Thomas, Jr.