Student Work

Pride Parades in Tupelo, Starkville, and Oxford

An MFA Thesis Project

Photos and text by Ellie Campbell

In May of 2016, Oxford, MS, held its first LGBTQ+ Pride parade in recent memory. Around 400 people (myself included) marched from the Depot in the Gertrude Ford Center parking lot, up University Avenue, through the square, and down West Jackson. Several hundred more people turned out on the square to cheer on the parade. That first Oxford Pride was part of a wave of LGBTQ+ celebrations that popped up in Mississippi beginning in 2015 and 2016 and continue to the present day. Hattiesburg had their first in the fall of 2015, then Oxford, then Jackson in the fall of 2016.

Biloxi, Cleveland, Gulfport, Ocean Springs, and more followed close behind. Though the pandemic forced many to cancel or go online, communities across Mississippi have continued to organize Pride parades and other celebrations of LGBTQ+ identities since 2015, a marked contrast from earlier periods. Bigger parades might pull several hundred marchers and spectators, while smaller events like drag shows, movie nights, church events, and reading groups provide space for anyone looking to participate or learn more.

For this MFA thesis project, I documented three Pride events in north Mississippi: Tupelo’s first in fall 2018, Starkville’s second in spring 2019, and Oxford’s first after the onset of the pandemic, in the summer of 2021. In a state often depicted as actively hostile to queer people, these Pride events make queer southern communities visible in new ways, while also revealing limitations in understanding and organizing around queerness in the South.

The three cities that I documented for this project speak to this new level of visibility, consequences for that visibility, and what it takes to keep that work going in different ways. Tupelo demonstrates the need to see queer community in a different way – a mix of quiet accommodation and circulating networks transformed into a highly visible but temporary takeover of public space, showing that queer folks are here but also allowing for a negotiation of visibility. Starkville experienced the potential consequences of the shift, which brought both institutional discrimination and outright right-wing protest. But that same heightened visibility, though it came with pushback, inspired more Pride events. Though I wrote about Tupelo first in this project, their first Pride event was partly a result of Starkville’s troubles; Melanie Deas, the director of Tupelo’s Link Centre, brought up Starkville in her conversation with their mayor when asking if he would push back in the same way as the other city’s aldermen. Oxford Pride started even earlier and inspired those in Starkville and others across the state.

This wave of LGBTQ+ Pride events in Mississippi presents a counter to a number of negative stereotypes about queer life in the South: that it is inhospitable to LGBTQ+ people; if anyone who is queer does live there, they suffer under constant oppression; that anyone who identifies as queer leaves the state as soon as it is possible to do so; and that queer life and communities only exist in large urban areas, few if any in the South. National reporting on queer life in Mississippi echoes and reinforces these narratives; media outlets primarily run stories where queer life is under siege, often from fringe right-wing groups, and do not bother to report on successful LGBTQ+ events that proceed peacefully and without opposition.

Of course, there are many aspects of life in Mississippi that are inhospitable to queer individuals and communities. The state is one of the most political and socially conservative in the nation. There are no legal protections in the state for queer Mississippians unless they are provided by federal law, and some state laws explicitly allow for discrimination, like the Religious Liberty Accommodations Act (aka HB 1523). The state passed an anti-gay marriage constitutional amendment in 2004 with an 86 percent majority. There are no housing or employment nondiscrimination laws and no hate crime laws specifically protecting LGBTQ+ individuals. The state did not issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples until forced to by Obergefell v. Hodges, a 2015 U.S. Supreme Court decision.

The past few years have seen a vast increase in the number of anti-LGBTQ+ state legislation introduced across the country; 2021 had a record 250 bills introduced at the state level and 2022 is currently on track to surpass that number. In 2022 alone, legislators in Mississippi have introduced bills that restrict healthcare for transgender youth, mandate single sex bathrooms by gender identity determined at birth, exclude transgender youth from sports, restrict transgender people from acquiring identification that accurately reflects their gender, and more.

Mississippi is nevertheless home to many queer individuals, who go to work and come home, who raise children and go to church, who enjoy drag shows and trips to bars in Memphis and New Orleans, who throw potluck and pool parties for their friends, who run for office and go to school and vacation on the coast, and who build joyful lives and supportive communities, even under these difficult circumstances.

Documenting Pride parades and events in Mississippi helps us hold both of these truths at the same time: the state can be both an oppressive place for queer Mississippians and a space of joy. Focusing on these events foregrounds the strength and joy of the community without forgetting or erasing the violence or despair.

- A sticker (Y'all means all) and a button (They, them, theirs) on a tie-dyed t-shirt

- An exhibit by the University Baptist Church of Starkville, MS during Starkville Pride

- For sale: Hearts crocheted with rainbow yarn with fabric labels (I'm here, I'm queer) in plastic sleeves

Tupelo: A Different Kind of Visibility

WATCH: Tupelo Pride (a documentary short directed by Ellie Campbell)

Tupelo is a small city in north Mississippi with a population of about forty thousand people, with the population of the city plus the three surrounding counties hitting around 140,000. Located on Highway 78 and Interstate 22, it was once a center of furniture manufacturing, but now its economy relies largely on health care, retail, and banking. Tupelo is most famous as the birthplace of Elvis Presley, who was born in the eastern part of the city in 1935. A large Toyota plant is located about ten miles west in Blue Springs, Mississippi, and employs several thousand people. Tupelo is also known as the home of the American Family Association, a fundamentalist right-wing Christian non-profit that advocates on public policy, including opposing LGBTQ+ rights, abortion, and pornography. The AFA owns over 200 right-wing radio stations across the U.S. and Canada, and is best known for coordinating boycotts and protests of American media. The best-known depiction of queer life in/around Tupelo, the documentary film Small Town Gay Bar, shows that the bar was located outside of Tupelo in nearby Shannon, Mississippi, and takes some pains to show the isolation of the community.

Visibility is a key concern in LGBTQ+ history and queer studies and has real consequences for how we understand queer life in Mississippi. The South and rural spaces remain understudied in this literature, which often focuses on major American urban areas like New York and San Francisco. Early histories root their analysis of the appearance of queer identity in urban modernity and look to institutions that cater exclusively to particular identities – like gay and lesbian bars and clubs, queer coffeeshops, gay bookstores, gay neighborhoods, etc.

- A vintage neon sign points toward Tupelo's business district

Other academic works privilege national organizing efforts, like the legal fights to repeal sodomy laws, fight for gay marriage, or engage with other types of discriminatory laws and actions. These studies root their understanding of queer identity formation in urban modernity, what Halberstam termed “metronormativity.” The academic work that does exist on the South argues for the necessity of using other methods to see queerness – not just explicitly queer identities and spaces in urban areas - but the way that queer desire is possible at all times in all places, but shaped by the specificities of location.

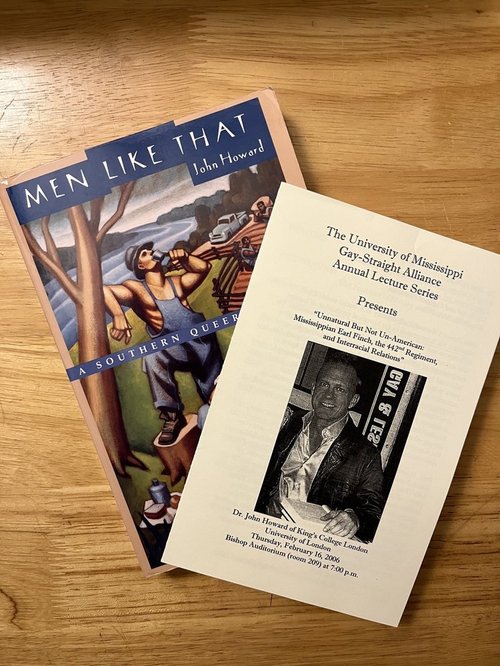

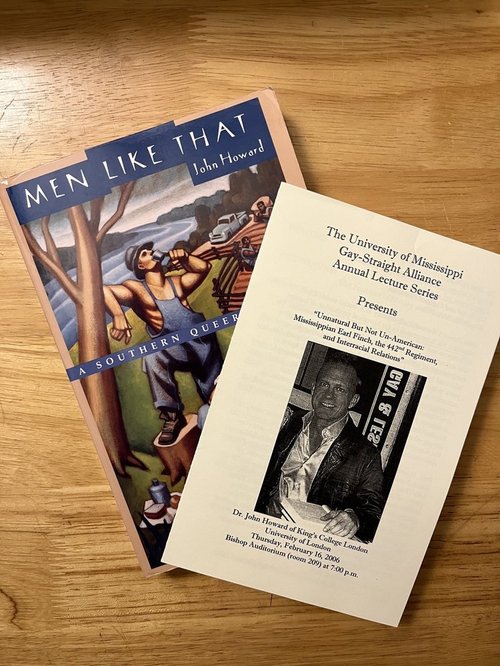

John Howard’s groundbreaking Men Like That: A Southern Queer History argues that queer life in the mid-twentieth century was an “open secret” in Mississippi. A code of silence and the advantages of kinship allowed for queer Mississippians to be tolerated, so long as they were not open about their identities or activities and did not challenge white supremacist power structures. Howard terms this “quiet accommodation” and documents the ways in which it sometimes gave way to more overt and active oppression, often as a backlash to the rise of other social movements like the Civil Rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 70s. (xix-xx) While that culture of “quiet accommodation” still exists in Mississippi, and there are still those who do not openly identify as LGBTQ+ who nevertheless have queer desire or participate in same-sex sex, queer identities have become more visible, and to a limited extent more accepted, in recent years.

In Coming Out of the Magnolia Closet: Same-Sex Couples in Mississippi, John F. Marszalek uses Howard’s concept of quiet accommodation or “social compact of silence” to read and understand the more recent oral histories he collected with gay and lesbian Mississippians in long term romantic relationships. (31) Marszalek found both similarities and differences from Howard’s construction; “throughout the couples’ stories a theme of tolerance but not acceptance is revealed; an unspoken admonition to live quietly, not act ‘too gay,’ and not demonstrate any displays of affection.”

Many oral histories gathered by University of Mississippi students track a small but significant LGBTQ+ community and set of spaces; Rick Gladish and PJ Newton describe a long history of gay bars in and around the city, several of which they worked at or owned. Most served a small community across the region that drove long distances to come to the bars; Gladish notes that for Tupelo-area bars, “even though Columbus was an hour away, it was still technically competition.” Having more than one bar split the queer customer base of northeast Mississippi and made it even more difficult for them to operate. Both Gladish and Newton worked full time jobs while owning or running gay bars in the area.

- A variation of the classic rainbow flag hangs from a Tupelo balcony

- For sale: Tupelo Pride t-shirts

Beyond the bars, Tupelo is also home to spaces that are queer-friendly, if not specifically for queer people, like the Link Center that hosts PFLAG meetings or other bars and clubs that provide space for an occasional drag show. Many of the bars that Gladish and Newton describe were out in the county, or in smaller towns near Tupelo or Columbus. Looking at the oral histories and the kinds of networks that Howard describes, these experiences and spaces are all mostly on the fringe or impermanent, tucked away in less visible spaces or the privacy of people’s homes.

Cecelia Parks’ recent essay, “‘Be Nice to My Shadow:’ Queer Negotiation of Privacy and Visibility in Kentucky,” examines the complex strategies undertaken by queer people to give them control over visibility of their queerness. Not everyone is comfortable enough, or privileged enough, or safe enough, to be seen as queer, not just known as queer. This negotiation of privacy and visibility renders the historical record incomplete; the interviewees in the oral histories she consults are out and visible enough to participate in a queer oral history archive. Like Howard’s consideration of “men who like that” as well as “men like that,” those who are less visible nevertheless deserve attention. Bars out in the county or occasional drag shows or community meetings in Tupelo give people a way to manage when they are seen as queer, letting them navigate that line with more private spaces where they could be more open about their identity.

- Parade goers watch a drag performance in the park

None of this work fully explains a full Pride celebration on “Tupelo’s front porch,” Fair Park, in front of City Hall, in the middle of downtown, attended by several hundred people draped in rainbows. Staking a claim to the heart of a city and loudly celebrating LGBTQ+ people breaks from the model of “quiet accommodation” for a new kind of visibility.

At the same time, it represents a continuation of the work the same community members have been doing all along. Documenting Pride events allows for a window into a larger community, even if, like those missing from Parks’ oral history collections or Howard’s “men who like that,” the entire landscape of queer desire is not immediately represented.

The ephemerality of these events – they might take up a week or long weekend once or twice a year – demonstrates the presence, acceptance, and support of and for queer Mississippians where permanent and permanently visible structures are lacking. Pride parades are both shaped by material conditions – lack of resources and critical mass of concentrated urban population for permanent and visible queerness – and also shape the material circumstances for their own gain.

We might not have a gay neighborhood or a lesbian bar, but we can have a party in the Grove. We can drape a Pride flag on the Elvis statue for an afternoon. We can wrap rainbows around a cowbell and ring it as loudly as possible, for the span of a parade.

- Pride Parade goers walking in Tupelo, MS

- Parade Grand Marshall Eric White, also known as Godiva Holliday, addresses the Tupelo crowd.

Starkville: The Consequences of Visibility

- A rainbow cowbell in Starkville, MS

Unlike Oxford and Tupelo’s first Pride events, Starkville’s did not proceed without major controversy. At worst, Oxford usually had a couple of counter-protesters who would show up with handwritten cardboard signs and stand by the Confederate statue on the south side of the courthouse. Tupelo’s first Pride event had a couple of kids stand across the street with a similar sign. At one point during the very hot and sunny day, a volunteer ran across the street to offer him a bottle of water, and he refused to take the “gay water,” and that was the worst thing that happened and the only encounter anyone had with him all day.

That doesn’t mean that communities weren’t prepared; Melanie Deas, one of the Tupelo organizers, worked with the police department on the security, and they “had the entire SWAT team surrounding Fair Park waiting for something horrible to happen.” Fortunately, nothing did. Oxford organizers have also coordinated with the city and campus police; parade permits run through the city police department, and the police are present for events for traffic control and other security issues. Neither city has experienced much in the way of public problems, regardless of whatever might be happening behind the scenes. Unfortunately, Starkville had a very different experience.

- Protestors along the Starkville Pride parade route

When the local organization Starkville Pride, then led by president Bailey McDaniel, applied for a parade permit with the city in early 2018, the city’s board of aldermen initially voted no, 4-3. The organization’s members were devastated, and the refusal turned national media attention to the city.

In Starkville, the process of acquiring a parade permit runs through the Board of Aldermen. As in most other cities in Mississippi, they are directly elected from separate districts or wards in the city. Unlike Oxford or Tupelo, which run permits through local agencies like the city police or Borad of Tourism, Starkville has elected representatives vote directly to approve whether someone can have a parade. The board had already faced a controversy over LGBTQ+ in 2014; they passed a nondiscrimination ordinance but repealed it several months later due to local pressure. The alderman had also experienced a kind of visibility and community pressure associated with LGBTQ+ organizing, and had chosen to become part of the problem instead of searching for solutions.

Visibility is a key issue in LGBTQ+ studies generally, and in this project specifically. Visibility is often offered as a solution for the social, political, and cultural problems facing the LGBTQ+ community, certainly as a route to self-knowledge but also as a way to address many other issues. The popularity of Pride events is partly based on this; it is literally about celebrating queer identities openly.

But being visibly queer, not just known as queer but also seen as queer, is more accessible for some members of the community than others. Other axes of privilege still hold; being white, cis-gendered, having a stable job and/or housing, inheriting family wealth, having access to decent health care, etc., all affect how “out” and visible people are able to be. For example, the growing social awareness of the existence of trans people has been met with a broad backlash of conservative politicians trying to enact bills targeted as trans folks.

- Starkville Pride Parade in motion

Work on trans identities, particularly trans women of color, pays careful attention to the problem of visibility. In their article “(Trans)Gendering Abolition: Black Trans Geographies, Art, and the Problem of Visibility,” Jaden Janak notes that “visibility, at least in the traditional sense, is a fraught project for trans people, whose moment of coming into visibility is often the moment of violence.” (259) Media visibility of trans people can render them both hypervisible and hyperinvisible at the same time by reducing them to stereotypes and statistics.

Visibility is a key way for LGBTQ+ people to gain self-knowledge – communities don’t exist without people being able to understand themselves and identify with each other in some way. But visibility opens up people to violent or oppressive responses. And those responses fall most heavily on the most marginalized people, which is why work about and by trans women of color focuses so heavily on it.

The trade-offs of increased visibility help make sense of what happened in Starkville. At the moment when the LGBTQ+ community became most visible to a governing structure – elected officials whose activities are subject to public scrutiny rather than less visible city agencies – is the moment where backlash becomes a viable response. When queer folks broke the social compact to stay quiet, their accomodation vanished.

The denial of the permit, the subsequent outcry, and the lawsuit combined to draw national attention. Newspapers like the New York Times ran stories, as did the regional and local newspapers. As Janak points out, this coverage rendered queer people in Mississippi both hypervisible and hyperinvisible; national attention was briefly focused on Starkville, but the coverage largely fell into tired tropes about oppressed, isolated LGBTQ+ people in a hostile world. That attention also attracted fringe right-wing religious protesters, who showed up with bullhorns and giant signs.

Some coverage was given to allies and others in support networks, but it was largely individualized and did not represent the larger communities or social divides. None of it understood the longer history of queer life in the state. Once the board of aldermen reversed their decision, the attention dried up. Few if any outside the state were still paying attention the next year. Starkville’s second parade was a resounding success; they had no trouble getting a permit and had events planned for the whole week. The right-wing religious groups showed up again, but were largely ignored by marchers.

This is one of the reasons that I wanted to tackle this project; local communities deserved better representation. If Pride is about visibility, even in the face of backlash, then at least we should be visible as full people and full communities, not a stereotype made up to fuel someone else’s agenda.

- For sale: Starkville Pride t-shirts

- O'Hara Productions had a tent at Starkville Pride

- For sale: Coffee and desserts

- On stage: GoDiva Holliday

- A disco ball added to the ambience

An exhibit by the University Baptist Church of Starkville, MS during Starkville Pride

For sale: Hearts crocheted with rainbow yarn with fabric labels (I'm here, I'm queer) in plastic sleeves

- The Starkville Pride parade as seen from a balcony

Oxford: Sustaining Visibility With Queer Joy

- For sale: Oxford Pride hats and t-shirts for Godiva Holliday

Oxford currently has the longest running annual Pride event in north Mississippi. In 2015, Matt Kessler, then a graduate student at the University of Mississippi, worked with the Isom Center to organize the first Pride parade in Oxford in recent years. A small group had a small Pride march in the late 1990s, but felt discouraged after the attempt and did not try again. The 2015 parade was more successful; several hundred people showed up to march and a few hundred more lined the streets (especially on the square, where, in true Oxford fashion, they could have drinks on the balconies of several of the city’s bars).

Kessler had worked with the Isom Center the year before to organize a showing of Small Town Gay Bar and a subsequent drag show at the Lamar Lounge that featured queens from the film. That event was also a huge success. No one had any idea beforehand what kind of response it would get, but the event filled the Lamar Lounge to capacity with an even longer line of folks waiting outside.

- Printed program for John Howard speaking at the University of Mississippi in February 2006 and a copy of his book Men Like That: A Southern Queer History

LGBTQ+ organizing at the University of Mississippi had been going on for years. Like Tupelo and Starkville, there had always been some kind of queer community or network in Oxford. Gay house parties or lesbian potlucks, welcoming Unitarian Universalist church services, hanging out at queer-friendly bars like Jubilee or the Blind Pig, speakers like John Howard or Judy Shepard or Dustin Lance Black on campus, student socials with the GSA or UM Pride Network, and more provided space for meeting fellow LGBTQ+ friends or partners, discovering and negotiating and identity, and building community.

But like Tupelo and Starkville, putting on a full Pride parade through the middle of the square in Oxford – or later holding an event in the Grove on campus – was a degree of visibility that went beyond what had come before.

Why a Pride parade? Given the challenges and the potential for backlash, why did queer Mississippians begin organizing Pride parades and other events in 2015 and 2016?

Part of the reason might lie in a number of controversies in the years immediately preceding this organizing. Major events on the national, state, and local level threw queerness into stark relief and made queer existence in Mississippi more overtly political than it had been before.

On the national level, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down their decision to legalize gay marriage in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015, which kicked off both jubilant celebrations and a right-wing backlash. Preceded by U.S. v. Windsor in 2013, which struck down portions of the federal Defense of Marriage Act and allowed the federal government to recognize same-sex marriage, Obergefell struck down state laws preventing same-sex marriage under the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Politicians in many southern states, Mississippi included, quickly responded. Governor Phil Bryant and Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves both spoke out against the decision; other lawmakers openly discussed the possibility that the state might refuse to grant any marriage licenses.

Meanwhile, many same-sex couples in Mississippi took advantage of their new rights and got married.

The backlash was not confined to the issue of marriage; Mississippi legislators began considering the “Religious Freedom Accommodations Act,” otherwise known as HB 1523, in February of 2016. The bill protects people and organizations who have a “sincerely held religious belief or moral conviction” that “marriage is or should be recognized as the union of one man and one woman; sexual relations are properly reserved to such a marriage; and male (man) and female (woman) refer to an individual’s immutable biological sex as objectively determined by anatomy and genetics at time of birth.”

In other words, a bakery doesn’t have to make someone a gay wedding cake if they don’t want to, which they didn’t have to do anyway before the bill was passed. The law had other, more insidious consequences: organizations could fire a single mother who got pregnant, adoption agencies could refuse to place a child with a same-sex couple, doctors could refuse health care to a trans patient, and more. National media covered the bill’s passage and subsequent legal cases and asserted the same tropes about abject Mississippians at the mercy of an oppressive state.

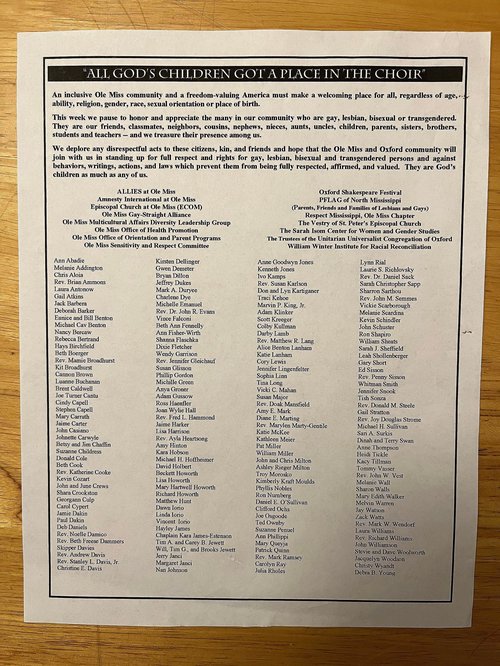

In Oxford, recent local events had also galvanized the queer community. In 2013, even before Obergefell, the University of Mississippi’s campus endured yet another controversy, this time over the play The Laramie Project. On October 1, 2013, a performance of the play was disrupted by heckling from a group of about twenty football players. Actors later reported that comments were made about not only sexuality, but also weight and race. Dozens of staff, faculty, and students signed letters in the student newspaper, like the one to the right, in support of the queer community. The university issued its usual tepid response, held a few town halls that let off steam but didn’t result in any actual action, and called it a day. The football players were largely protected by the university, and many in the queer community felt abandoned by the institution.

In the wake of Obergefell backlash, increased legislation targeted at discriminating against queer communities, and local campus controversies, it’s little wonder that queer Mississippians felt the need to stand up, proclaim their presence, celebrate their identities, and lay claim to central, public, visible space in the state. But while anger and defiance are absolutely cornerstones of Pride events, they aren’t the only emotions expressed there. Queer joy is a key part of Pride events.

- All God's Children Got a Place in the Choir: a statement in support of inclusivity in the Ole Miss/Oxford community

Queer joy is rarely a focus in any discussions of LGBTQ+ life, whether in mainstream media or academia, much less in anything focused on the South. Narratives about queer life are often framed by negative experiences: oppression, isolation, loneliness, violence. In The Promise of Happiness, Sara Ahmed explores the idea of the “unhappy queer” as a part of queer genealogy and affect. She argues that stories about both queer happiness and unhappiness matter, but that is depends on what kind of story is being told. Conventional narratives construct queer life as an unhappy because it is “a life without the ‘things’ that make you happy, or as a life that is depressed as it lacks certain things: ‘a husband, children.’” But unhappiness in the face of an unjust world can be a method for imagining different, better worlds. And committing to joy in the face of injustice can be a method for sustaining resistance.

Stef Shuster and Laurel Westbrook’s “Reducing the Joy Deficit in Sociology: A Study of Transgender Joy,” pushes back against sociological scholarship’s “focus on negative experiences and inequality” by interviewing transgender people about their experiences of joy in their identity. They found four major themes: “1) the value of asking about joy, 2) the joy of being from a marginalized group, 3) the improvement of quality of life, and 4) the increased connections with others.” Both emphasize the power of collective identity, and how the experience of joy can motivate people towards change.

Pride events give participants and observers a collective sense of belonging and positive emotion, a marked contrast to the stereotypical feelings of isolation and oppression so often attributed to the condition of being queer. Fun, laughter, happiness, and joy are a means to mobilize people as well as criticize and ridicule the opposition to Pride.

Centering joy as a key part of Pride in Mississippi does a number of things. It helps us better understand the community by combating oversimplified stereotypes depicting queer life in the state as oppressed and abject. It helps explain why people keep organizing Pride parades and events even in the face of many challenges. And it gives us an argument for why we should keep these events going.

Though many of the narrative portions of this project do highlight the challenges that the queer community in Mississippi faces, I hoped to provide a contrast to this with film and photography. The overwhelming emotional experience of going to Pride in Mississippi is one of happiness, solidarity, support, and joy. These positive experiences are a key part of mobilizing people to imagine and fight for a better world, one in which queer Mississippians are not just tolerated, but fully accepted as a visible, valued part of society. We cannot ignore the challenges, but we do ourselves a grave disservice if we forget the joy.

- Water bottles decorated with flowers and DIY labels

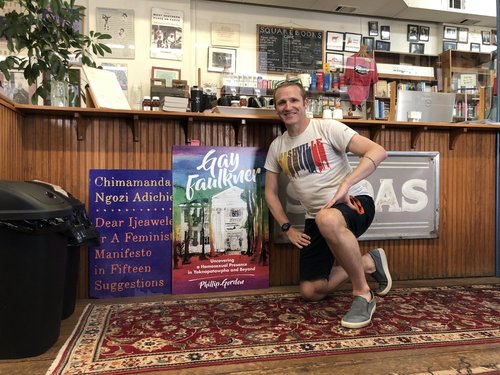

- Pip Gordon poses with a poster for his monograph, Gay Faulkner, at Square Books

- A view from a tent with a rainbow flag of the Grove stage where a band is playing

- Miss Oxford Pride 2020 blows a kiss from the parade route

- A bystander wears a rainbow flag like a superhero cape (written on flag: I love girls and boys)

- A poster at an information table: "No pigs at pride"

- Silhouette of a performer lit by a spotlight

- A crowd watches performers on stage lit by a spotlight

- The Oxford Police Department had a tent in Information Alley

- How to join the Human Rights Campaign of Mississippi? Text JOIN to 472-472

- The Human Rights Campaign of Mississippi was in Information Alley

- The University of Mississippi was supportive of the day's events

- For sale: t-shirts and hats for the day's event, Out in the Grove: A Pride Celebration

- A young woman used eye shadows to create her own rainbow

- A queer couple kisses under the entrance to the Walk of Champions in the Grove

Bibliography & Thanks

- A shelf of scholarly sources

- Printed program for John Howard speaking at the University of Mississippi in February 2006 and a copy of his book Men Like That: A Southern Queer History

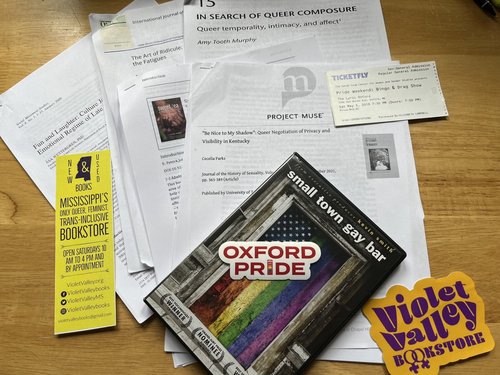

- A pile of printed articles, a DVD copy of Small Town Gay Bar, and local stickers

Books and Articles

ACLU, “Legislation Affecting LGBTQ Rights Across the Country,” https://www.aclu.org/legislation-affecting-lgbtq-rights-across-country (Updated weekly, last accessed July 2022).

Associated Press, “Jackson’ First LGBT Pride: ‘It Was Much Love,’” Jackson Free Press, June 13, 2016. https://www.jacksonfreepress.com/news/2016/jun/13/jacksons-1st-lgbt-pride-parade-it-was-much-love/

Boyd, Nan Alamilla and Horacio N. Roque Ramirez. Bodies of Evidence: The Practice of Queer Oral History. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Bravmann, Scott. Queer Fictions of the Past: History, Culture, and Difference. Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Bruce, Katherine McFarland. Pride Parades: How a Parade Changed the World. NYU Press, 2016.

Carreon, Cristina, “Tupelo Hosts Inaugural Pride Festival in Fairpark,” October 7, 2018. https://www.djournal.com/news/local/tupelo-hosts-inaugural-pride-festival-in-fairpark/article_e09f4fc3-d880-5e0b-aa6a-5640a3651dc7.html

D’Emilio, John and Estelle Freedman. Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. 2nd ed., University of Chicago Press, 1997.

Decker, Julia Sonder. The Invisible Orientation: An Introduction to Asexuality. Skyhorse Press, 2015.

Gray, Mary L. Out in the Country: Youth, Media, and Queer Visibility in Rural America. NYU Press, 2009.

Harker, Jaime. The Lesbian South: Southern Feminists, the Women in Print Movement, and the Queer Literary Canon. University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Howard, John. Men Like That: A Southern Queer History. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Janak, Jaden. “(Trans)gendering Abolition: Black Trans Geographies, Art, and the Problem of Visibility,” A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Vol. 28, Issue 2, 2022.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South. University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Black. Queer. Southern. Women.: An Oral History. University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Marszalek, John F. Coming Out of the Magnolia Closet: Same-Sex Couples in Mississippi. University of Mississippi Press, 2020.

Mitchell, R. P., “The Art of Ridicule: Queer Black Joy in the Face of the Fatigues,” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 35, issue 2, 1-17, February 2022.

Murphy, Heather, “How a Pastor and a Popcorn Shop Owner Helped Save Pride in Starkville,” June 21, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/21/us/pride-starkville-mississippi.html

Parks, Cecilia. “’Be Nice to My Shadow:’ Queer Negotiation of Privacy and Visibility in Kentucky.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, vol. 30, issue 3, 363-389, 2021.

Rucker, LaRecca, “Pride Parade Rolls on the Square,” Oxford Eagle, May 8, 2016. https://www.oxfordeagle.com/2016/05/08/pride-parade-rolls-on-the-square/

Shuster, Stef M. and Laurel Westbrook, “Reducing the Joy Deficit in Sociology: A Study of Transgender Joy.” Social Problems, 1-19, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spac034

Stone, Amy L. “The Geography of Research on LGBTQ Life: Why Sociologists Should Study the South, Rural Queers, and Ordinary Cities.” Sociology Compass, 2018.

Strunk, Kamden K, Leslie Ann Locke, and Georgianna L. Martin. Oppression and Resistance in Southern Higher and Adult Education: Mississippi and the Dynamics of Equity and Social Justice. Palgrave Macmillian, 2017.

Websites and Organizations

Capital City Pride, https://mscapitalcitypride.org

Glitterary Festival, https://glitteraryfestival.com/schedule

Invisible Histories Project, https://invisiblehistory.org

Queer Mississippi Oral History Project, https://egrove.olemiss.edu/queerms/

The Sarah Isom Center for Women and Gender Studies, https://sarahisomcenter.org

The Spectrum Center, https://hattiesburgpride.com/

Starkville Pride, http://www.starkvillepride.com

Tupelo Pride, https://www.facebook.com/tupelopride/

Violet Valley Bookstore, https://www.violetvalley.org/

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the Center for the Study of Southern Culture, the Southern Documentary Project, Violet Valley Bookstore, and everyone who invests their time, labor, money, and love into Mississippi Pride.

- A close up of the face of the Elvis Presley statue wearing the rainbow flag as a cape

Seeing Queer Joy in Mississippi: Pride Parades in Tupelo, Starkville, and Oxford

Contact: ercampbell535@gmail.com