Mississippians

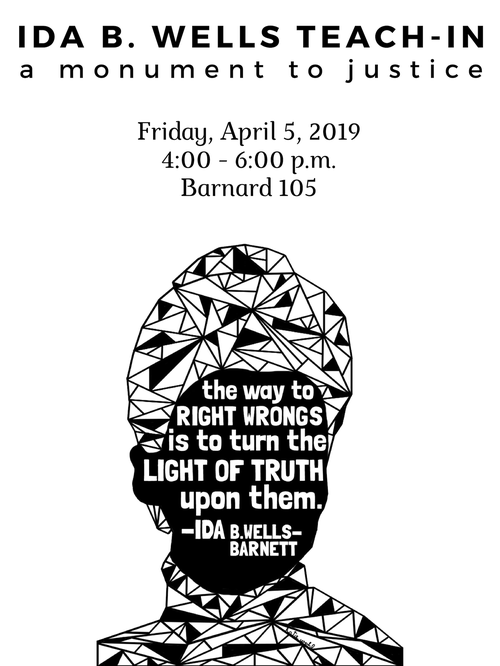

The Ida B. Wells exhibit accompanied the "Ida B. Wells Teach-In: A Monument to Justice" held by the Arch Dalrymple III Department of History on April 5, 2019. The event included historical contextualization by UM's Dr. Shennette Garrett-Scott, an appearance by Michelle Duster (Wells’ great-great granddaughter), a performance by the UM Gospel Choir, and a short film on Wells’ life.

The exhibit was originally created for the 2nd floor display case by Cecelia Parks, Research and Instruction Librarian and Assistant Professor; Dr. Garrett Felber, Assistant Professor of History; Rhondalyn Peairs, heritage tour guide; Victoria Merchant, Ph. D. student in the Department of English.

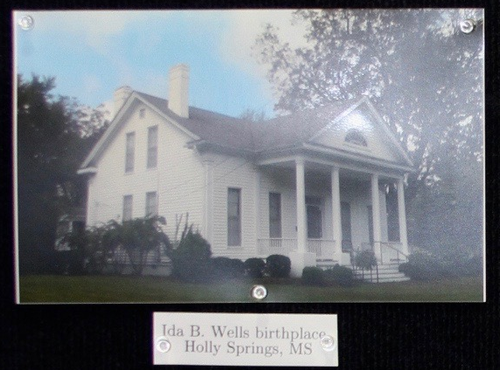

Early Life

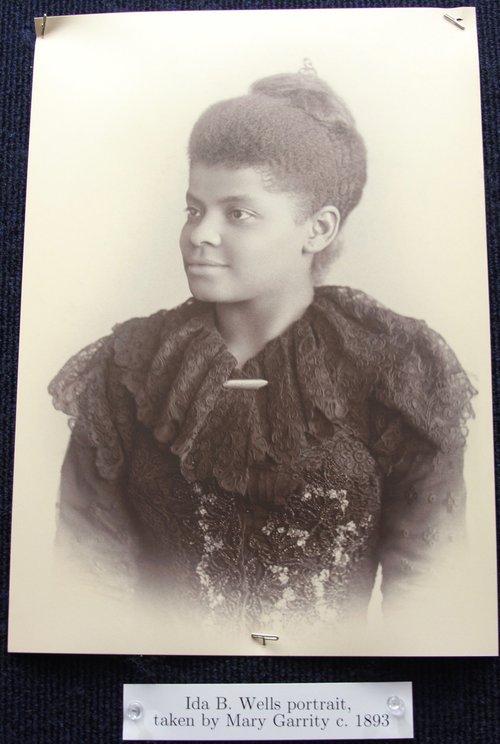

Ida Bell Wells was born in 1862, six months before the Emancipation Proclamation, to James and Elizabeth Wells in Holly Springs, Mississippi. Her father was the son of a slave owner and an enslaved woman; he worked as a carpenter and later in local Reconstruction politics. Her Mother, Elizabeth Wells, was a well-known local cook. Ida received her early education in the grammar school of Shaw University (now Rust), and she later studied at Fisk University and the Lemoyne Institute.

Both of her parents died in a yellow fever epidemic in 1878, orphaning Ida at age 16 and leaving her in charge of her siblings. She moved the family to Memphis to live with an aunt and work as a teacher and write for the Free Speech, a black newspaper in Memphis.

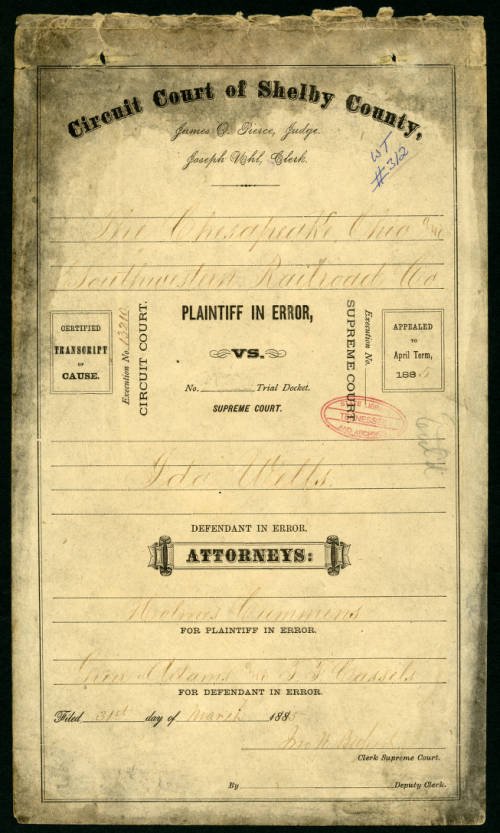

In 1884, Ida was forcibly ejected from a train for refusing to move to a segregated car. She sued the railroad and won a $500 award, though the decision was later overturned.

Family Life

In 1895, Wells married Ferdinand L. Barnett, a lawyer and editor from Chicago who was eventually appointed assistant state attorney for Cook County. Wells-Barnett had four children and was a devoted wife and mother while continuing her political activism and journalism career.

Death and Posthumous Honors

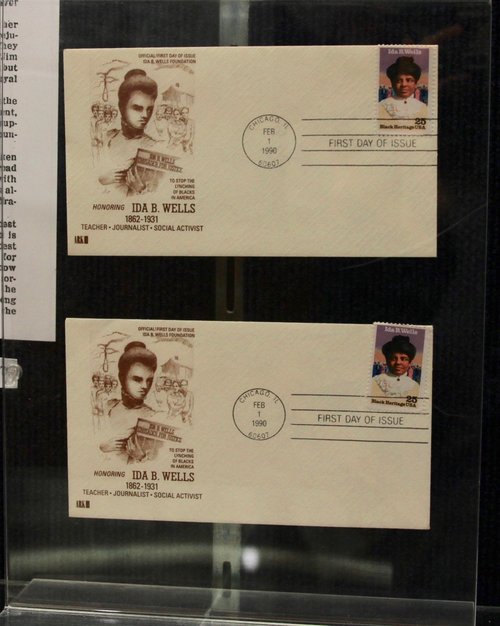

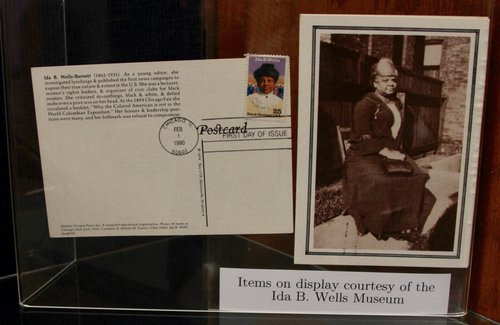

In 1931 Ida B. Wells-Barnett died in Chicago of uremia at the age of 69. To honor her after her death, a low income housing project was named after her in Chicago in 1941, she was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1998, and a commemorative stamp bearing her likeness was issued by the U. S. Postal Service in 1990.

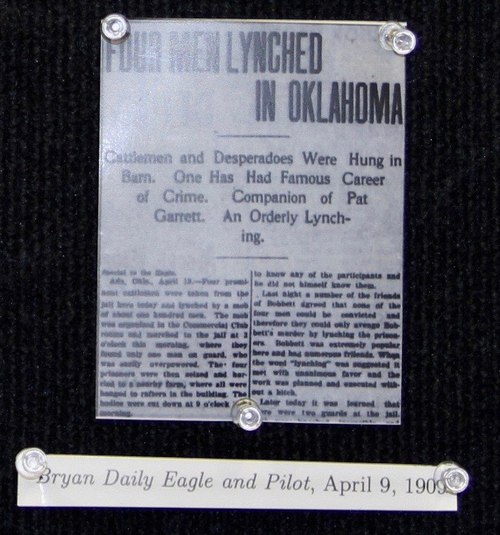

It wasn't until the late 1960s that regular lynchings gradually stopped.

Antilynching Campaign

Wells' long fight against lynching began in 1889, when three young black businessmen and close friends of hers (Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Henry Steward) were lynched in a Memphis suburb. This event deeply affected Wells, who began to use her journalistic platform to fight lynching.

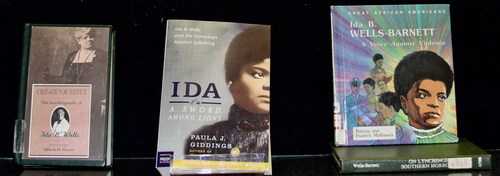

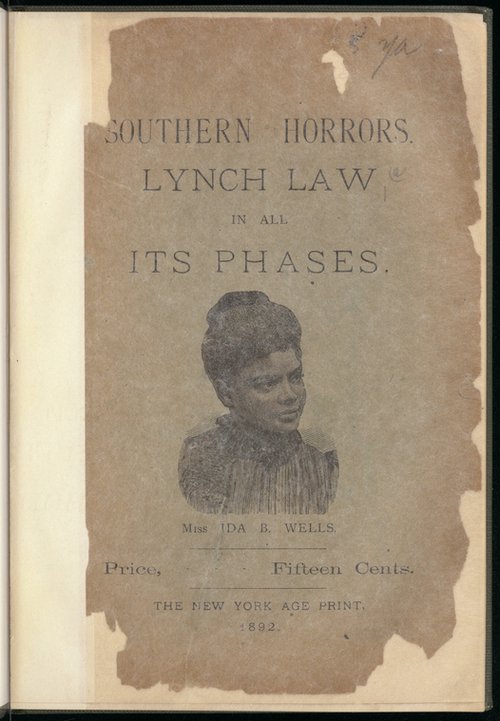

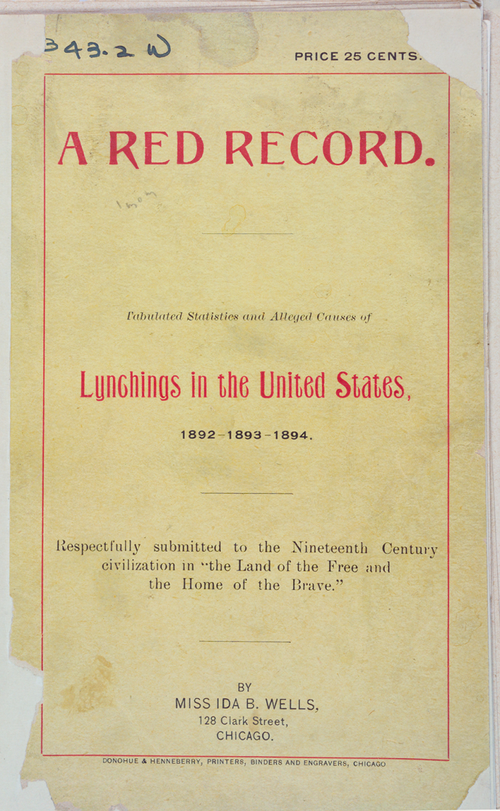

In 1892, Wells wrote an impassioned article for The New York Age newspaper, which turned into a longer pamphlet titled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases. She published A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States, the first statistical study of lynching in the post-Emancipation south, in 1895. She continued to campaign against lynching through lectures in the north and went on a European tour, lecturing on the horrors of lynching.

Activism

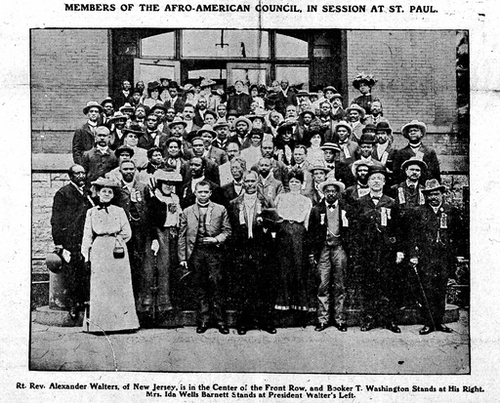

Wells-Barnett served as secretary of the National Afro-American Council, founded in 1898, and headed its Antilynching Speaker Bureau. Wells began researching and writing about lynching in 1889. She published and gave lectures all over the United States and Europe on the topic.

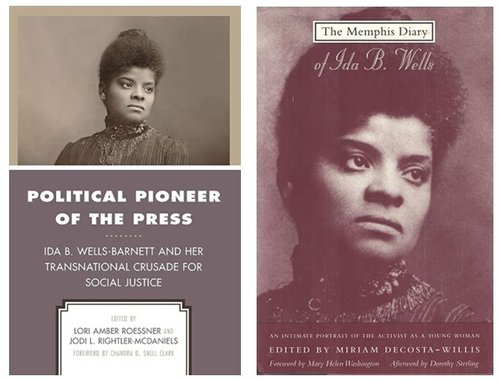

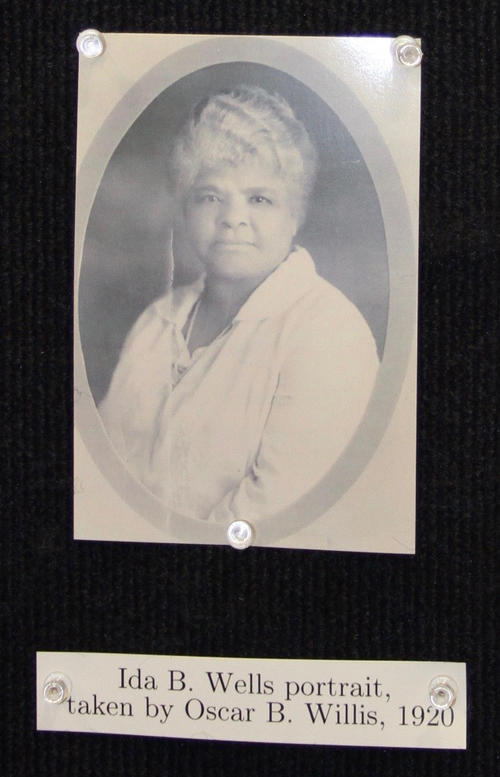

(Photo from Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to her antilynching activism, Wells-Barnett was involved in the African American club movement. She helped found the National Afro-American Council, National Association of Colored Women, and the Negro Fellowship League, which provided housing and employment for black male migrants. She was also involved in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

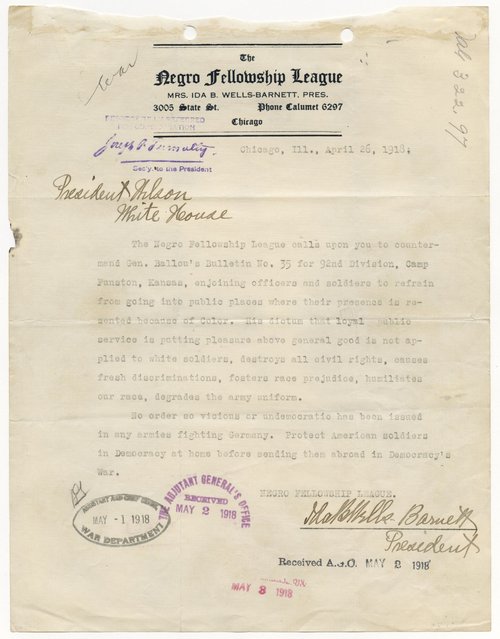

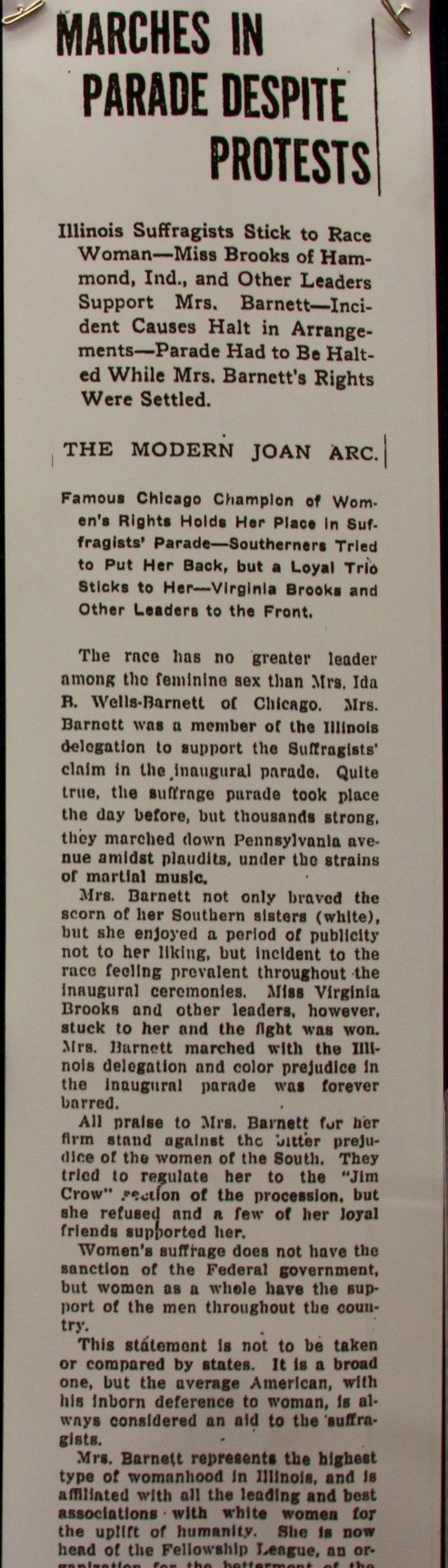

Wells-Barnett continued her activism in Chicago and on the national stage. She and her husband challenged the restrictive housing on Chicago's East Side white community. She became the first black woman probation officer in the country out of concern for the welfare of Chicago's black community. She also organized the first black women's suffrage club in Illinois and marched with suffragists in Washington, D. C., integrating the march itself. (Below: letter to President Woodrow Wilson protesting the treatment of black troops, 1918)

Wells-Barnett published her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, in 1928. She ran, unsuccessfully, for the Illinois state legislature, one of the first African American women ever to run for public office.