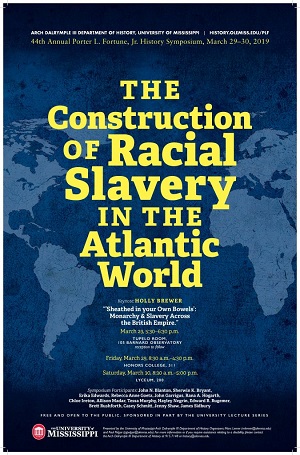

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

African Slave Trade Monopolies and the Suppression of Native Slavery in the Americas

Document Type

Event

Location

Lyceum 200

Start Date

30-3-2019 10:15 AM

End Date

30-3-2019 11:00 AM

Description

During the first 150 years of American colonization, Europeans enslaved far more indigenous Americans than people of African descent. During the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, enslaved Native Americans mined more gold, planted and harvested more tobacco and sugar, and extracted more natural resources—especially pearls and dyewoods—than enslaved Africans. Yet by the later seventeenth century African slaves came to dominate in nearly all key areas of plantation production. If enslaved Indians were foundational to the colonial systems they built, if they “worked” as enslaved laborers, why in these places, and why in general, was there a transition from enslaving Indians to enslaving Africans? And why then?

Recent research has made these questions harder, not easier, to answer. There used to be two widely-held assumptions for why Indian slavery “failed” and African slavery “succeeded.” One was cultural, often bordering on racial: suggesting that Africans “made better slaves” than their Amerindian counterparts. The other had to do with disease, suggesting that enslaved Indians disappeared in disease epidemics, forcing European colonists to turn to the transatlantic slave trade to supply their growing demand for coerced laborers. Neither of these explanations has held up very well under closer scrutiny. Other answers are emerging, focused especially on the legal and geopolitical realities of West African versus Amerindian relations with Europeans. But few have looked closely at the investors, traders, and regulatory officials actually making these decisions to see when and why they channeled their investments from one enslaved population to another.

This essay explores these financial motives by looking closely at the French Compagnie du Sénégal, and comparing its operations to the English Royal African Company. During the sugar boom of the 1670s and 1680s, investors in France’s Compagnie du Sénégal paid a band of Dutch privateers to intercept shipments of enslaved Natives en route from mainland South America to Martinique. They justified the attacks by arguing that the selling of Native slaves to French colonies violated their exclusive right to the slave trade, giving them authority to protect their contractual monopoly by force. The merchants selling the enslaved Natives demanded compensation, appealing to the French governor of the Caribbean colonies to force their attackers to restore their losses. This paper uses this dispute to explore two important, but understudied, aspects of Caribbean slavery in the seventeenth century. First, it traces the routes and volume of Native slave trades from northern South America to the Lesser Antilles, focused on the French islands but gesturing beyond them. Second, it shows how African slave trading companies, by actively suppressing competing slave trading networks, played an important role in diminishing Native American slavery, suggesting new and important ways of thinking about the relationship between Native and African slaveries in the early modern Americas.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Rushforth, Brett, "African Slave Trade Monopolies and the Suppression of Native Slavery in the Americas" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 11.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/11

African Slave Trade Monopolies and the Suppression of Native Slavery in the Americas

Lyceum 200

During the first 150 years of American colonization, Europeans enslaved far more indigenous Americans than people of African descent. During the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, enslaved Native Americans mined more gold, planted and harvested more tobacco and sugar, and extracted more natural resources—especially pearls and dyewoods—than enslaved Africans. Yet by the later seventeenth century African slaves came to dominate in nearly all key areas of plantation production. If enslaved Indians were foundational to the colonial systems they built, if they “worked” as enslaved laborers, why in these places, and why in general, was there a transition from enslaving Indians to enslaving Africans? And why then?

Recent research has made these questions harder, not easier, to answer. There used to be two widely-held assumptions for why Indian slavery “failed” and African slavery “succeeded.” One was cultural, often bordering on racial: suggesting that Africans “made better slaves” than their Amerindian counterparts. The other had to do with disease, suggesting that enslaved Indians disappeared in disease epidemics, forcing European colonists to turn to the transatlantic slave trade to supply their growing demand for coerced laborers. Neither of these explanations has held up very well under closer scrutiny. Other answers are emerging, focused especially on the legal and geopolitical realities of West African versus Amerindian relations with Europeans. But few have looked closely at the investors, traders, and regulatory officials actually making these decisions to see when and why they channeled their investments from one enslaved population to another.

This essay explores these financial motives by looking closely at the French Compagnie du Sénégal, and comparing its operations to the English Royal African Company. During the sugar boom of the 1670s and 1680s, investors in France’s Compagnie du Sénégal paid a band of Dutch privateers to intercept shipments of enslaved Natives en route from mainland South America to Martinique. They justified the attacks by arguing that the selling of Native slaves to French colonies violated their exclusive right to the slave trade, giving them authority to protect their contractual monopoly by force. The merchants selling the enslaved Natives demanded compensation, appealing to the French governor of the Caribbean colonies to force their attackers to restore their losses. This paper uses this dispute to explore two important, but understudied, aspects of Caribbean slavery in the seventeenth century. First, it traces the routes and volume of Native slave trades from northern South America to the Lesser Antilles, focused on the French islands but gesturing beyond them. Second, it shows how African slave trading companies, by actively suppressing competing slave trading networks, played an important role in diminishing Native American slavery, suggesting new and important ways of thinking about the relationship between Native and African slaveries in the early modern Americas.