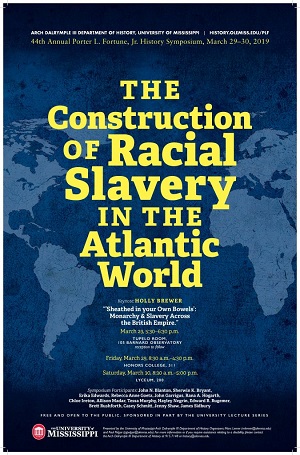

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

The Unbridled Greed of the Conquistadors: The Real Provisión of 1530 and the Legality of Native Enslavement in the Southern Caribbean

Document Type

Event

Location

Honors College 311

Start Date

29-3-2019 9:45 AM

End Date

29-3-2019 10:30 AM

Description

Spanish settlers in the New World began enslaving Native people immediately after the 1492; by 1498 there was a brisk trade in enslaved Native people in the Greater Antilles and in Spain itself. Ferdinand and Isabella confronted questions about the legality of Native enslavement in a series of reales cédulas, or royal charters, attempting to limit enslavement to Native people who were suspected of cannibalism or who resisted Spanish authority and conversion to Christianity. Despite these efforts, Spanish settlers continued to enslave Native people with impunity. Further efforts to prevent most acts of enslavement and to ensure humane treatment of Native people in 1512, 1513, and again in 1526 also failed to rein in slaving. The Real Provisión of 1530 went further than any previous law regarding Native enslavement, prohibiting Spanish settlers from taking “any Indian as a slave either in a just war or otherwise, nor through rescate, nor purchase, nor trade, nor through any other means, even though they may be Indians who held, hold, or may hold other Indians among them as slaves.”

This paper contextualizes the Provisión by examining a group of wealthy slavers and slave traders who shifted their base of operations from the Santo Domingo to what is presently the coast of Venezuela and Colombia in the late 1520s. I argue that exposure of their slaving activities in part led to the promulgation of the Provisión. Slavers from Cubagua and the coasts of Cumaná and Paria led a fierce opposition to the Provisión; for example, the royal official responsible for registering and publicizing new laws on Cubagua refused to publish the Provisión, and continued to license slave-raiding expeditions. As the Venezuelan historian Morella Jiménez has noted, “the Provisión of 1530 was never implemented.” I argue the failure of the Provisión was due to the highly coordinated lobbying effort slave raiders and slave traders mounted in the Spanish court to ensure it was never enforced.

Examining the context in which the Provisión was written, as well as the resistance to it, exposes the darkest aspects of Spanish colonialism. When settlers failed to generate wealth through gold, silver, or pearls, they turned to slaving as their primary mode of making money. These well-organized networks of merchants, slavers, and settlers were able to easily combat even the most desultory efforts at regulating their slaving activities. The Provisión, though, did not vanish. Some of its text later reappeared, word-for-word, in the New Laws of 1542, in which the Spanish Crown outlawed most aspects of the enslavement of Native people in its dominions in the New World.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Goetz, Rebecca Anne, "The Unbridled Greed of the Conquistadors: The Real Provisión of 1530 and the Legality of Native Enslavement in the Southern Caribbean" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 12.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/12

The Unbridled Greed of the Conquistadors: The Real Provisión of 1530 and the Legality of Native Enslavement in the Southern Caribbean

Honors College 311

Spanish settlers in the New World began enslaving Native people immediately after the 1492; by 1498 there was a brisk trade in enslaved Native people in the Greater Antilles and in Spain itself. Ferdinand and Isabella confronted questions about the legality of Native enslavement in a series of reales cédulas, or royal charters, attempting to limit enslavement to Native people who were suspected of cannibalism or who resisted Spanish authority and conversion to Christianity. Despite these efforts, Spanish settlers continued to enslave Native people with impunity. Further efforts to prevent most acts of enslavement and to ensure humane treatment of Native people in 1512, 1513, and again in 1526 also failed to rein in slaving. The Real Provisión of 1530 went further than any previous law regarding Native enslavement, prohibiting Spanish settlers from taking “any Indian as a slave either in a just war or otherwise, nor through rescate, nor purchase, nor trade, nor through any other means, even though they may be Indians who held, hold, or may hold other Indians among them as slaves.”

This paper contextualizes the Provisión by examining a group of wealthy slavers and slave traders who shifted their base of operations from the Santo Domingo to what is presently the coast of Venezuela and Colombia in the late 1520s. I argue that exposure of their slaving activities in part led to the promulgation of the Provisión. Slavers from Cubagua and the coasts of Cumaná and Paria led a fierce opposition to the Provisión; for example, the royal official responsible for registering and publicizing new laws on Cubagua refused to publish the Provisión, and continued to license slave-raiding expeditions. As the Venezuelan historian Morella Jiménez has noted, “the Provisión of 1530 was never implemented.” I argue the failure of the Provisión was due to the highly coordinated lobbying effort slave raiders and slave traders mounted in the Spanish court to ensure it was never enforced.

Examining the context in which the Provisión was written, as well as the resistance to it, exposes the darkest aspects of Spanish colonialism. When settlers failed to generate wealth through gold, silver, or pearls, they turned to slaving as their primary mode of making money. These well-organized networks of merchants, slavers, and settlers were able to easily combat even the most desultory efforts at regulating their slaving activities. The Provisión, though, did not vanish. Some of its text later reappeared, word-for-word, in the New Laws of 1542, in which the Spanish Crown outlawed most aspects of the enslavement of Native people in its dominions in the New World.