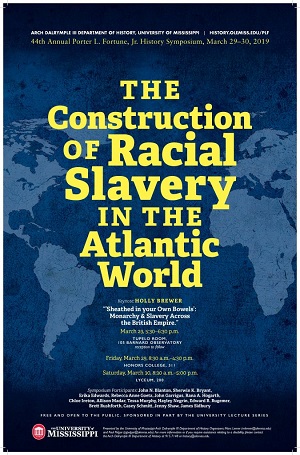

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

First Enslavements and First Emancipations: Slavery and Capitalism in Early Colonial Virginia, 1547-1660

Document Type

Event

Location

Lyceum 200

Start Date

30-3-2019 8:30 AM

End Date

30-3-2019 9:15 AM

Description

Scholars have long argued for the importance of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia in 1619 as a crucial moment in early American history. Often overlooked, however, is another event that transformed colonial Virginia in that year. In colonial America’s first emancipation, Governor George Yeardley freed all servants held by the Virginia Company, encouraging them to take up individual freeholds and establish private households. This decision cemented the patriarchal domus as the basic unit of social and economic organization in the colony and, as numerous scholars have noted, set the stage for the development of chattel slavery. Rooted in absolutist conceptions of private property and domestic authority, Virginia enslavers proscribed the ability of their human property to appeal to outside authorities, rendering slaves legal non-persons subject to the sole dominion of slaveholding patriarchs.

But the patriarchal household was no monolith, and slavery’s place within it was by no means predetermined. Often associated with the dissenting Protestantism and political anti-absolutism typical of 17th century Massachusetts, other Britons drew on a potent corporatist tradition that saw all household dependents, even the enslaved, as legal persons entitled to the basic protections of the law. This nascent antislavery argument urged the state to interpose its authority in all household relations, bracketing the power of all patriarchs—even kings—under the rule of law and protecting the bodies of all persons subject to its dominion. Often overlooked by previous scholars, this insistence on state mediation of household relations culminated in the first explicit denunciation of chattel slavery in the English language and influenced the social realities of slavery on the ground in the Bay Colony.

This paper argues that the legal status of the enslaved in early colonial Anglo-America was shaped by the conflict between these conceptions of household organization—an absolutist-individualist insistence that slaves were property versus a corporate-humanist ideal of universal personhood. It seeks to broaden our understanding of the relationship between slavery and capitalist development by demonstrating that the household was the incubator of both modern slavery and nascent forms of “free labor.” Through an examination of legal, political, and religious treatises, colonial and metropolitan statutes, and court cases in England, Virginia, and Massachusetts, it illustrates how this conflict played out in the peculiar local contexts of the Old Dominion and the Bay Colony, setting the future of slavery in England’s first mainland colonies on fundamentally different trajectories. It further argues that enslaved and free people of color were active agents in this early capitalist structure, not only rejecting it through flight or rebellion, but also insinuating themselves within it as heads-of-household, forcing both Virginia and Massachusetts to grapple with questions of slavery and black personhood. The fact that they resolved these questions in profoundly different ways is a testament to the divergent possibilities embedded within.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Blanton, John, "First Enslavements and First Emancipations: Slavery and Capitalism in Early Colonial Virginia, 1547-1660" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 15.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/15

First Enslavements and First Emancipations: Slavery and Capitalism in Early Colonial Virginia, 1547-1660

Lyceum 200

Scholars have long argued for the importance of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Virginia in 1619 as a crucial moment in early American history. Often overlooked, however, is another event that transformed colonial Virginia in that year. In colonial America’s first emancipation, Governor George Yeardley freed all servants held by the Virginia Company, encouraging them to take up individual freeholds and establish private households. This decision cemented the patriarchal domus as the basic unit of social and economic organization in the colony and, as numerous scholars have noted, set the stage for the development of chattel slavery. Rooted in absolutist conceptions of private property and domestic authority, Virginia enslavers proscribed the ability of their human property to appeal to outside authorities, rendering slaves legal non-persons subject to the sole dominion of slaveholding patriarchs.

But the patriarchal household was no monolith, and slavery’s place within it was by no means predetermined. Often associated with the dissenting Protestantism and political anti-absolutism typical of 17th century Massachusetts, other Britons drew on a potent corporatist tradition that saw all household dependents, even the enslaved, as legal persons entitled to the basic protections of the law. This nascent antislavery argument urged the state to interpose its authority in all household relations, bracketing the power of all patriarchs—even kings—under the rule of law and protecting the bodies of all persons subject to its dominion. Often overlooked by previous scholars, this insistence on state mediation of household relations culminated in the first explicit denunciation of chattel slavery in the English language and influenced the social realities of slavery on the ground in the Bay Colony.

This paper argues that the legal status of the enslaved in early colonial Anglo-America was shaped by the conflict between these conceptions of household organization—an absolutist-individualist insistence that slaves were property versus a corporate-humanist ideal of universal personhood. It seeks to broaden our understanding of the relationship between slavery and capitalist development by demonstrating that the household was the incubator of both modern slavery and nascent forms of “free labor.” Through an examination of legal, political, and religious treatises, colonial and metropolitan statutes, and court cases in England, Virginia, and Massachusetts, it illustrates how this conflict played out in the peculiar local contexts of the Old Dominion and the Bay Colony, setting the future of slavery in England’s first mainland colonies on fundamentally different trajectories. It further argues that enslaved and free people of color were active agents in this early capitalist structure, not only rejecting it through flight or rebellion, but also insinuating themselves within it as heads-of-household, forcing both Virginia and Massachusetts to grapple with questions of slavery and black personhood. The fact that they resolved these questions in profoundly different ways is a testament to the divergent possibilities embedded within.