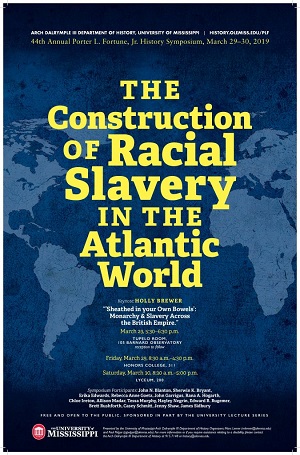

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

Black Loyalists in Sierra Leone and Black Royalism in the Revolutionary Atlantic

Document Type

Event

Location

Lyceum 200

Start Date

30-3-2019 4:15 PM

End Date

30-3-2019 5:00 PM

Description

I will begin with Jordan and Morgan and the way both framed the origins of racism within a move from seventeenth century Virginia to the founding of the United States, and did so in order to explore the shortcomings of the Founding (as a “paradox” for Morgan, or as a psychological failure writ large for Jordan). Both authors assumed that the Revolution was a fundamentally progressive event and that it’s problems rested on the exclusion of African-descended people. It would be too simple to say that they viewed that failure as simply a flaw—both insisted in different ways that the exclusions were so deeply rooted in American republicanism (and, by extension, in most Atlantic republicanism writ large) as to be constitutive elements in the founding. Both set up a story of American history as the struggle to overcome exclusions and thus make good on the promises of republican ideology. Black Loyalists, I will suggest, have always fit uneasily into this narrative. Most historians have explained their decision to side with the King’s forces in purely pragmatic terms; that they fought with whatever army offered them the best chance for freedom as individuals. Pragmatism certainly played a role in determining black allegiance, as it did in determining white allegiance. But recent research has uncovered mounting evidence that African and African descended people living through the Age of Revolution frequently sided with monarchies rather than republics. I will use a case study of black loyalism/monarchicalism in Sierra Leone in 1800 to suggest that we need to pay greater attention to the ideological (as opposed to pragmatic) appeal of monarchicalism to blacks in the Age of Revolution.

The case study involves an uprising by black settlers in Sierra Leone who the British had evacuated from New York City at the end of the Revolutionary War. Most were American born, and a plurality had been slaves in Virginia. They posted a set of “settlers’ laws” in Freetown to announce what turned out to be a short-lived rebellion against the authority of the Sierra Leone Company. It’s a fascinating document, reflecting much that they learned while living through the American Revolution. In fact, Sierra Leone Company officers made occasional comments about the degree to which the “Nova Scotians,” as the settlers called themselves, had been infected by republican doctrine. But the Nova Scotians did not seek independence. They sought instead to win recognition of their corporate rights within the British monarchical system. In this, they resemble many of their black contemporaries in societies as disparate as St. Domingue/Haiti, Jamaica, New Granada (present-day Columbia), Cuba and Brazil.

After offering a close reading of the 1800 uprising in Freetown, I will zoom back out to place it in this broader context and to ask what questions black monarchicalism raises for the way we think about the struggle between tradition and ‘modernity’—progress and reaction—in the Age or Revolution. To make that point I will close with a discussion of Toussaint Louverture and the appeal of black republicanism in St. Domingue/Haiti.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Sidbury, James, "Black Loyalists in Sierra Leone and Black Royalism in the Revolutionary Atlantic" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 17.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/17

Black Loyalists in Sierra Leone and Black Royalism in the Revolutionary Atlantic

Lyceum 200

I will begin with Jordan and Morgan and the way both framed the origins of racism within a move from seventeenth century Virginia to the founding of the United States, and did so in order to explore the shortcomings of the Founding (as a “paradox” for Morgan, or as a psychological failure writ large for Jordan). Both authors assumed that the Revolution was a fundamentally progressive event and that it’s problems rested on the exclusion of African-descended people. It would be too simple to say that they viewed that failure as simply a flaw—both insisted in different ways that the exclusions were so deeply rooted in American republicanism (and, by extension, in most Atlantic republicanism writ large) as to be constitutive elements in the founding. Both set up a story of American history as the struggle to overcome exclusions and thus make good on the promises of republican ideology. Black Loyalists, I will suggest, have always fit uneasily into this narrative. Most historians have explained their decision to side with the King’s forces in purely pragmatic terms; that they fought with whatever army offered them the best chance for freedom as individuals. Pragmatism certainly played a role in determining black allegiance, as it did in determining white allegiance. But recent research has uncovered mounting evidence that African and African descended people living through the Age of Revolution frequently sided with monarchies rather than republics. I will use a case study of black loyalism/monarchicalism in Sierra Leone in 1800 to suggest that we need to pay greater attention to the ideological (as opposed to pragmatic) appeal of monarchicalism to blacks in the Age of Revolution.

The case study involves an uprising by black settlers in Sierra Leone who the British had evacuated from New York City at the end of the Revolutionary War. Most were American born, and a plurality had been slaves in Virginia. They posted a set of “settlers’ laws” in Freetown to announce what turned out to be a short-lived rebellion against the authority of the Sierra Leone Company. It’s a fascinating document, reflecting much that they learned while living through the American Revolution. In fact, Sierra Leone Company officers made occasional comments about the degree to which the “Nova Scotians,” as the settlers called themselves, had been infected by republican doctrine. But the Nova Scotians did not seek independence. They sought instead to win recognition of their corporate rights within the British monarchical system. In this, they resemble many of their black contemporaries in societies as disparate as St. Domingue/Haiti, Jamaica, New Granada (present-day Columbia), Cuba and Brazil.

After offering a close reading of the 1800 uprising in Freetown, I will zoom back out to place it in this broader context and to ask what questions black monarchicalism raises for the way we think about the struggle between tradition and ‘modernity’—progress and reaction—in the Age or Revolution. To make that point I will close with a discussion of Toussaint Louverture and the appeal of black republicanism in St. Domingue/Haiti.