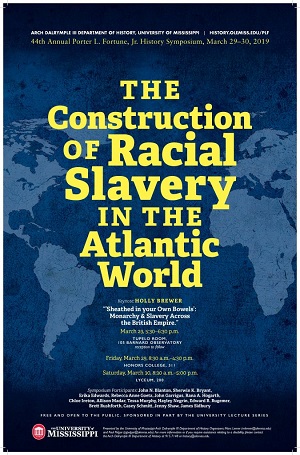

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

A Secret Among The Blacks, Of Which The Whites Know Nothing: The Political Vision Of Enslaved West Africans In 1750s Saint-Domingue

Document Type

Event

Location

Lyceum 200

Start Date

30-3-2019 3:30 PM

End Date

30-3-2019 4:15 PM

Description

How did Africans imagine the future of the Caribbean slave societies where they lived? In an extraordinary 1757 confession, a man enslaved in Saint-Domingue revealed that he and others were working to create a free black population large enough “to confront the whites if necessary.” In other words, they foresaw a time when free blacks would assert themselves, not against slavery necessarily, but against racial bias.

The 1757 confession came from Médor, who had spent 20 years enslaved to a physician and coffee planter. He declared to his master that the medicines he purchased from fellow West Africans had killed slaves and livestock on the plantation. He hoped his revelation would lead to the arrest of these “pernicious men”.

While describing how West Africans in his circle made and administered such substances, Médor divulged that he and others had been secretly dosing their masters for years, sharing drugs they believed would lead to their own manumission. White interrogators believed Médor and his colleagues were trying to poison their masters. The paper argues that an unidentified outbreak of anthrax likely struck down those Médor believed he had inadvertently killed. Médor and the other slaves accused of poisoning in subsequent weeks claimed that their medicines were intended to heal relationships, or even to cloud a master’s thinking, so he or she would commit to manumission. After two full days of interrogation, Médor committed suicide when he realized that colonists planned to burn him at the stake.

The last third of the paper describes how Médor’s confession changes our understanding of Saint-Domingue and then successful slave revolution it produced. In his 1980 book From Rebellion to Revolution, Eugene Genovese theorized that the Haitian Revolution was a turning point in slave uprisings. Before 1791 rebels sought to create African-style societies in the Americas while after the Haitian Revolution they focused on winning civil and human rights. Médor’s testimony shows that Genovese’s dichotomy is too stark. Thirty years before the Haitian Revolution, the West African foresaw a Saint-Domingue in which blacks would force whites to make changes in society. Slavery might still exist in that future world, but so many blacks would live in freedom that race would no longer define bondage.

In Médor’s Saint-Domingue, people of color made up only 20 percent of the free population. In 1790, their share had grown to nearly half. Many were former slaves, with family members still in bondage. The paper will describe the many factors that created this free black population and shaped its political goals. It argues that free blacks’ willingness to confront whites to transform their own place in society was an essential element in the success of the Haitian Revolution.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Garrigus, John, "A Secret Among The Blacks, Of Which The Whites Know Nothing: The Political Vision Of Enslaved West Africans In 1750s Saint-Domingue" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 2.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/2

A Secret Among The Blacks, Of Which The Whites Know Nothing: The Political Vision Of Enslaved West Africans In 1750s Saint-Domingue

Lyceum 200

How did Africans imagine the future of the Caribbean slave societies where they lived? In an extraordinary 1757 confession, a man enslaved in Saint-Domingue revealed that he and others were working to create a free black population large enough “to confront the whites if necessary.” In other words, they foresaw a time when free blacks would assert themselves, not against slavery necessarily, but against racial bias.

The 1757 confession came from Médor, who had spent 20 years enslaved to a physician and coffee planter. He declared to his master that the medicines he purchased from fellow West Africans had killed slaves and livestock on the plantation. He hoped his revelation would lead to the arrest of these “pernicious men”.

While describing how West Africans in his circle made and administered such substances, Médor divulged that he and others had been secretly dosing their masters for years, sharing drugs they believed would lead to their own manumission. White interrogators believed Médor and his colleagues were trying to poison their masters. The paper argues that an unidentified outbreak of anthrax likely struck down those Médor believed he had inadvertently killed. Médor and the other slaves accused of poisoning in subsequent weeks claimed that their medicines were intended to heal relationships, or even to cloud a master’s thinking, so he or she would commit to manumission. After two full days of interrogation, Médor committed suicide when he realized that colonists planned to burn him at the stake.

The last third of the paper describes how Médor’s confession changes our understanding of Saint-Domingue and then successful slave revolution it produced. In his 1980 book From Rebellion to Revolution, Eugene Genovese theorized that the Haitian Revolution was a turning point in slave uprisings. Before 1791 rebels sought to create African-style societies in the Americas while after the Haitian Revolution they focused on winning civil and human rights. Médor’s testimony shows that Genovese’s dichotomy is too stark. Thirty years before the Haitian Revolution, the West African foresaw a Saint-Domingue in which blacks would force whites to make changes in society. Slavery might still exist in that future world, but so many blacks would live in freedom that race would no longer define bondage.

In Médor’s Saint-Domingue, people of color made up only 20 percent of the free population. In 1790, their share had grown to nearly half. Many were former slaves, with family members still in bondage. The paper will describe the many factors that created this free black population and shaped its political goals. It argues that free blacks’ willingness to confront whites to transform their own place in society was an essential element in the success of the Haitian Revolution.