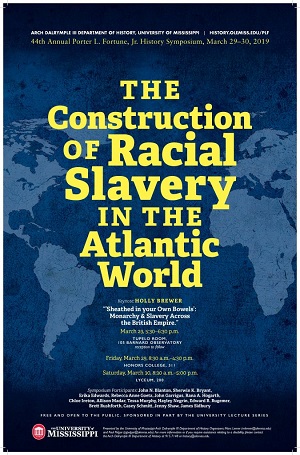

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

Reading Race and Framing Susceptibility in the American Atlantic

Document Type

Event

Location

Honors College 311

Start Date

29-3-2019 3:30 PM

End Date

29-3-2019 4:45 PM

Description

As the Atlantic trade in captive Africans grew, so too did opportunities for comparing their bodies against Europeans in the new disease environments of the Americas. By the time the trade peaked in the latter part of the eighteenth century, the American Atlantic became a disparate space that gave rise to new vocabularies that reframed the idea of race and offered new ways of seeing racial difference. These vocabularies, especially those that developed around differences between black and whites, became a bedrock on which policies of exclusion and subjugation were built. Black skin, for example, came to signal Africans’ supposed innate otherness and inferiority, and indicated who was enslaveable and who was not.

Yet it took more than differences in skin color and the creation of physiological characteristics to sustain the idea of race. Put plainly, racial differences had to be deeper than just the skin. Physicians, who lived and worked in the Atlantic World, were instrumental agents in creating the idea that racial differences did exist and were readily discernible when considered in relation to health. This process, which this paper takes up at length, was grounded in tenants of health and sickness that originated in antiquity. Physicians considered the interaction of climate, custom, habit, temperament, diet, and constitution in determining individual resistance or vulnerability to disease. As this paper shows, race as it came to be regarded as a specific category of human being that was based upon visually distinct traits, neatly fit into this framework. It was through this approach to understanding health that the concept of race was practically applied—that is, observed as a contributing factor to health outcomes in different types of bodies. References to the different ways black people seemed to resist certain diseases and not others appeared as offhand comments in letters, as topics of discussion in medical treatises, or as a detail in military medical reports. In other words, observed differences in sickness and health formed the clear proofs that physicians relied on in the process of making racial differences real. This attention to racial difference then, was not unthinking, nor was it calculated per se. Rather it emerged as a by-product of Eurocentric logic and out of an impulse to make sense of morbidity and mortality in new disease environments of the Americas.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Hogarth, Rana, "Reading Race and Framing Susceptibility in the American Atlantic" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 3.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/3

Reading Race and Framing Susceptibility in the American Atlantic

Honors College 311

As the Atlantic trade in captive Africans grew, so too did opportunities for comparing their bodies against Europeans in the new disease environments of the Americas. By the time the trade peaked in the latter part of the eighteenth century, the American Atlantic became a disparate space that gave rise to new vocabularies that reframed the idea of race and offered new ways of seeing racial difference. These vocabularies, especially those that developed around differences between black and whites, became a bedrock on which policies of exclusion and subjugation were built. Black skin, for example, came to signal Africans’ supposed innate otherness and inferiority, and indicated who was enslaveable and who was not.

Yet it took more than differences in skin color and the creation of physiological characteristics to sustain the idea of race. Put plainly, racial differences had to be deeper than just the skin. Physicians, who lived and worked in the Atlantic World, were instrumental agents in creating the idea that racial differences did exist and were readily discernible when considered in relation to health. This process, which this paper takes up at length, was grounded in tenants of health and sickness that originated in antiquity. Physicians considered the interaction of climate, custom, habit, temperament, diet, and constitution in determining individual resistance or vulnerability to disease. As this paper shows, race as it came to be regarded as a specific category of human being that was based upon visually distinct traits, neatly fit into this framework. It was through this approach to understanding health that the concept of race was practically applied—that is, observed as a contributing factor to health outcomes in different types of bodies. References to the different ways black people seemed to resist certain diseases and not others appeared as offhand comments in letters, as topics of discussion in medical treatises, or as a detail in military medical reports. In other words, observed differences in sickness and health formed the clear proofs that physicians relied on in the process of making racial differences real. This attention to racial difference then, was not unthinking, nor was it calculated per se. Rather it emerged as a by-product of Eurocentric logic and out of an impulse to make sense of morbidity and mortality in new disease environments of the Americas.