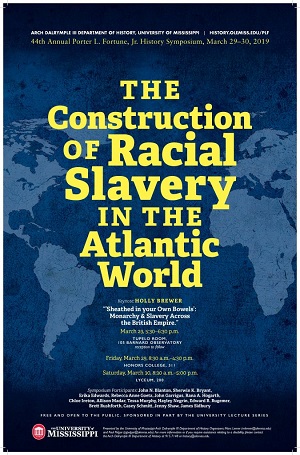

2019: The Construction of Racial Slavery in the Atlantic World

Ran Away From The Subscriber: Runaway Servants and Virginia’s Culture of Surveillance

Document Type

Event

Location

Honors College 311

Start Date

29-3-2019 2:30 PM

End Date

29-3-2019 3:15 PM

Description

Historians of slavery in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic often narrate the development of slave law as a counterpoint to the laws of servitude. They argue that as slavery expanded, not only did servitude decline, but the legal framework colonists developed to control slaves also made life more tolerable for those who remained temporarily bound. Citing legal codes that, beginning in the 1660s, drew ever greater distinctions between servants and the enslaved, these scholars assume that the racialization of bondage weakened masters’ power over white and mixed-race servants as it strengthened their power over slaves.

This chapter—as well as my larger book project—challenges these conclusions. Drawing on research in Virginia statutes and county court records, runaway ads, wills, estate inventories, and masters’ diaries and correspondence, “Ran Away from the Subscriber” demonstrates that, in many significant ways, the legal structures designed to control the enslaved also enhanced masters’ power over their servants, even as the institution of slavery expanded and the number of temporarily bound laborers decreased in eighteenth-century Virginia. The legal mechanisms put in place to identify, capture, and return runaway slaves were used to control servants in similar ways, and the laws themselves did not always distinguish between black slaves and white and mixed-race servants. Under certain circumstances large and middling planters differentiated even less. Masters of slaves often encouraged harsher restrictions on runaway servants, fearing servant-slave collusion and the undermining of masters’ power more generally. Moreover, the networks they established to return runaway slaves aided in the return of servants, as court justices, constables, and neighboring planters worked in support of servant-holding masters to thwart servants’ attempts to escape. As they fled bondage, then, servants found themselves ensnared in the same nets cast by the community to capture their enslaved counterparts. From established practices of advertisement and alert to elaborate protocols of detention, transportation, and payment, returning runaways—whether bound temporarily or for life—involved a wide swath of colonial society in the enforcement of masters’ legal power. By reconstructing these dynamics this chapter offers what could be called an ethnography of mastery, venturing well beyond statutes and magistrates to reveal the social, economic, and spatial dimensions of colonial legal power.

Masters leveraged the widespread establishment of permanent, racial slavery as a way to exploit those who remained temporarily bound. And despite the significant differences between the two institutions and the people bound to serve within them, a more explicit legal and structural parallel exists between these systems of labor than has been previously understood.

Relational Format

Conference Proceeding

Recommended Citation

Madar, Allison, "Ran Away From The Subscriber: Runaway Servants and Virginia’s Culture of Surveillance" (2019). Porter L. Fortune, Jr. Symposium. 5.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/plf/2019/schedule/5

Ran Away From The Subscriber: Runaway Servants and Virginia’s Culture of Surveillance

Honors College 311

Historians of slavery in the eighteenth-century British Atlantic often narrate the development of slave law as a counterpoint to the laws of servitude. They argue that as slavery expanded, not only did servitude decline, but the legal framework colonists developed to control slaves also made life more tolerable for those who remained temporarily bound. Citing legal codes that, beginning in the 1660s, drew ever greater distinctions between servants and the enslaved, these scholars assume that the racialization of bondage weakened masters’ power over white and mixed-race servants as it strengthened their power over slaves.

This chapter—as well as my larger book project—challenges these conclusions. Drawing on research in Virginia statutes and county court records, runaway ads, wills, estate inventories, and masters’ diaries and correspondence, “Ran Away from the Subscriber” demonstrates that, in many significant ways, the legal structures designed to control the enslaved also enhanced masters’ power over their servants, even as the institution of slavery expanded and the number of temporarily bound laborers decreased in eighteenth-century Virginia. The legal mechanisms put in place to identify, capture, and return runaway slaves were used to control servants in similar ways, and the laws themselves did not always distinguish between black slaves and white and mixed-race servants. Under certain circumstances large and middling planters differentiated even less. Masters of slaves often encouraged harsher restrictions on runaway servants, fearing servant-slave collusion and the undermining of masters’ power more generally. Moreover, the networks they established to return runaway slaves aided in the return of servants, as court justices, constables, and neighboring planters worked in support of servant-holding masters to thwart servants’ attempts to escape. As they fled bondage, then, servants found themselves ensnared in the same nets cast by the community to capture their enslaved counterparts. From established practices of advertisement and alert to elaborate protocols of detention, transportation, and payment, returning runaways—whether bound temporarily or for life—involved a wide swath of colonial society in the enforcement of masters’ legal power. By reconstructing these dynamics this chapter offers what could be called an ethnography of mastery, venturing well beyond statutes and magistrates to reveal the social, economic, and spatial dimensions of colonial legal power.

Masters leveraged the widespread establishment of permanent, racial slavery as a way to exploit those who remained temporarily bound. And despite the significant differences between the two institutions and the people bound to serve within them, a more explicit legal and structural parallel exists between these systems of labor than has been previously understood.