The Morality of Interstellar Messaging

Loading...

Start Date

14-12-2020 9:20 AM

End Date

14-12-2020 9:40 AM

Description

We humans cannot yet confirm that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the cosmos. Such confirmation is not needed, however, to show that we should proceed carefully in our attempts to contact intelligent life, taking seriously the moral issues at play. As moral agents, different individuals and groups have different roles to play in this project, and these roles partially determine the details of their moral responsibilities. We begin by addressing those whose actions make humanity’s existence more noticeable, which will lead to questions of how best to evaluate, coordinate, and regulate such actions. The US military and METI International are both taking actions that increase chances of discovery. But there is an interesting difference between the two. While both pinging asteroids and sending directed transmissions to other planets are beacons of a sort, only METI intends to make contact with intelligent life. Intuitively, it seems to make a difference whether harmful effects are outright intended or merely foreseen. If it does make a difference, then it also makes a difference in how we should approach the morality of METI International’s choices versus the US military’s choices. One might challenge that by noting that METI proponents do not intend the harm they’re risking; they intend benefit. Instead of granting a moral pass to METI proponents, this challenge brings to light another serious moral concern. To both intend benefit and foresee harm in the very same effect is to engage in a kind of irrationality. Regarding risks of harm, some may believe that it is so unlikely that we will contact ETI through current messaging practices that it is not important to curb or debate these practices at this time. Even so, we show that small risks are nonetheless impermissible when the harm risked is great. And because the harm that METI is risking is serious and global in nature, we are justified in prescribing risk-minimizing behaviors to those whose actions intend to make our presence more noticeable. In turn, we ought to create and enforce practices that minimize the likelihood of harm. This leads directly to an analysis of which rules and regulations are appropriate here, and how we should appropriately implement and enforce any sanctions. Future generations do not exist, and there currently exists no entity tasked with enforcing protections against the risks of messaging. We should not act recklessly with respect to the welfare of future persons who are not in a position to advocate for their own wellbeing. We conclude that we ought to form a global, collaborative, adaptable, and accountable body tasked with formulating and enforcing the appropriate rules and regulations for messaging and coordinating messaging activities.

Recommended Citation

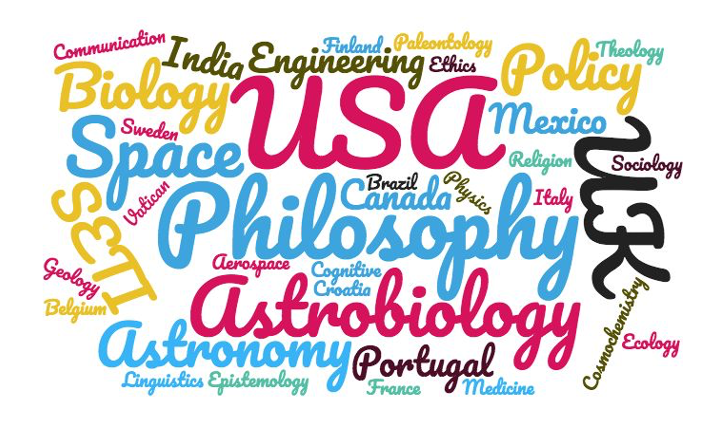

DeMarines, Julia and Haramia, Chelsea, "The Morality of Interstellar Messaging" (2020). Society for Social and Conceptual Issues in Astrobiology (SSoCIA) Conference. 2.

https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ssocia/2020/schedule/2

The Morality of Interstellar Messaging

We humans cannot yet confirm that intelligent life exists elsewhere in the cosmos. Such confirmation is not needed, however, to show that we should proceed carefully in our attempts to contact intelligent life, taking seriously the moral issues at play. As moral agents, different individuals and groups have different roles to play in this project, and these roles partially determine the details of their moral responsibilities. We begin by addressing those whose actions make humanity’s existence more noticeable, which will lead to questions of how best to evaluate, coordinate, and regulate such actions. The US military and METI International are both taking actions that increase chances of discovery. But there is an interesting difference between the two. While both pinging asteroids and sending directed transmissions to other planets are beacons of a sort, only METI intends to make contact with intelligent life. Intuitively, it seems to make a difference whether harmful effects are outright intended or merely foreseen. If it does make a difference, then it also makes a difference in how we should approach the morality of METI International’s choices versus the US military’s choices. One might challenge that by noting that METI proponents do not intend the harm they’re risking; they intend benefit. Instead of granting a moral pass to METI proponents, this challenge brings to light another serious moral concern. To both intend benefit and foresee harm in the very same effect is to engage in a kind of irrationality. Regarding risks of harm, some may believe that it is so unlikely that we will contact ETI through current messaging practices that it is not important to curb or debate these practices at this time. Even so, we show that small risks are nonetheless impermissible when the harm risked is great. And because the harm that METI is risking is serious and global in nature, we are justified in prescribing risk-minimizing behaviors to those whose actions intend to make our presence more noticeable. In turn, we ought to create and enforce practices that minimize the likelihood of harm. This leads directly to an analysis of which rules and regulations are appropriate here, and how we should appropriately implement and enforce any sanctions. Future generations do not exist, and there currently exists no entity tasked with enforcing protections against the risks of messaging. We should not act recklessly with respect to the welfare of future persons who are not in a position to advocate for their own wellbeing. We conclude that we ought to form a global, collaborative, adaptable, and accountable body tasked with formulating and enforcing the appropriate rules and regulations for messaging and coordinating messaging activities.